May 6, 2024

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. This month, Benjamin Burger discusses recent news about connected vehicles. Jerome Greco reviews the investigation by the FCC leading to its order of approximately $200 million in fines against wireless service carriers. Diane Akerman explains the progress of legislation banning the use of biometric surveillance. Finally, our guest columnist, Sidney Thaxter, explores litigating a case that involve automated license plate readers.

The Digital Forensics Unit of The Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of The Legal Aid Society.

In the News

The Dream of Connected Cars is a Privacy Nightmare

Benjamin S. Burger, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

People intuitively understand the connectivity of a cell phone or tablet. Consumers have had decades to become comfortable with mobile devices. While the United States still lacks a comprehensive privacy law, people appear to have a rudimentary sense that online browsing is not always secure or private. However, as more technology products become “connected” in the sense that they are generating and collecting user data, consumers are left unaware of how their movements and actions are being tracked.

Recent articles have revealed the tremendous amount of data generated by vehicles and sent to manufacturers. Even worse, these manufacturers, specifically GM, have been selling consumer data to third parties like data brokers and insurance companies. Many GM drivers have seen their insurance rates rise because of the data collected and sold by GM. Notably, this data isn’t even accurate. In a follow-up article, a New York Times reporter noted that because her husband was the “primary” owner of the vehicle, any data generated by the car was presumed to be when he was driving. Driving habits that can raise insurance premiums - like hard braking or rapid acceleration - cannot be tracked to the correct driver. Moreover, even the consent for data collection is hidden by salespeople, buried in lengthy privacy policies, or obscured by dark patterns.

Unfortunately, the options available to privacy-concerned consumers are limited. You can refuse to share data with your vehicle manufacturer, but this causes a few problems. First, over-the-air recalls (made famous by Tesla) are convenient for consumers. No one wants to take their car to a dealer for a software upgrade. Second, diagnostic information about a car is also helpful for the owner. Knowing why a “check engine” light turns on before you go to a mechanic saves time and stress. Third, trying to opt out of data sharing may be inconvenient or ineffective. Additionally, disabling the systems that “connect” a vehicle could void a warranty, damage the car, or hurt resale value.

Consumers should be aware that their vehicles are generating a tremendous amount of data, which can include highly personal information about locations and driving habits. Until consumers have a way to control this data and exert ownership over it, they will have to be vigilant in preventing surveillance capitalism from acquiring more information about their daily lives.

The FCC Fines Wireless Carriers Almost $200 Million

Jerome D. Greco, Digital Forensics Supervising Attorney

Last week, the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) announced [PDF] fines for cellular service providers, totaling close to $200 million. The fines are the culmination of an investigation into the selling of customers’ location data without their consent. The location information was sold to other companies, who would then offer access to law enforcement agencies with minimal to no safeguards. The FCC has fined AT&T $57.3 million, Sprint $12.2 million, T-Mobile $80.1 million, and Verizon $46.9 million. Sprint and T-Mobile merged in 2020.

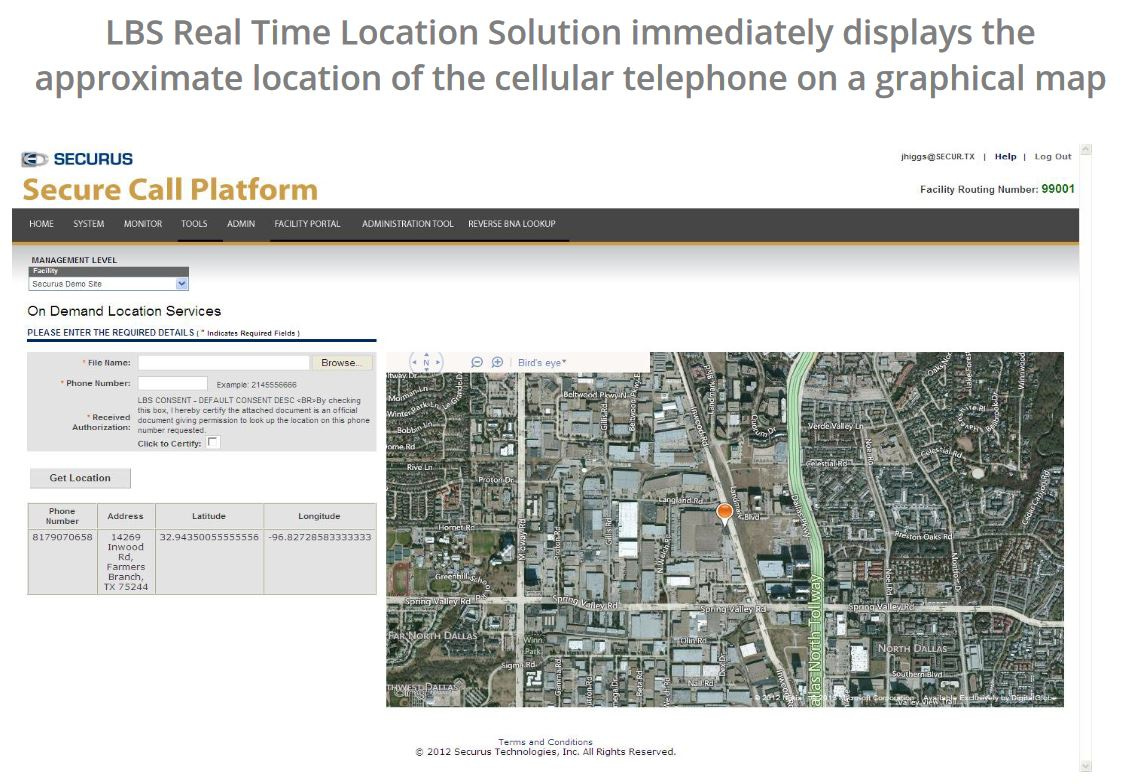

The investigation was initiated by a letter [PDF] to the FCC from Senator Ron Wyden in 2018. Wyden had urged the agency to investigate Securus Technologies, the infamous provider of phone services in correctional facilities and surveillance technology used to spy on the calls of incarcerated people. Securus was selling access to location data it received from 3Cinteractive, a mobile marketing company, to police. 3Cinterative obtained the data from location aggregator LocationSmart, who had purchased it from cell phone service companies. Multiple layers of corporate indifference to cellular service customers’ privacy was necessary for this level of intrusion to occur.

As revealed by Krebs on Security, LocationSmart was so careless with its location data that at one time it offered a free demo service that allowed “anyone to see the approximate location of their own mobile phone, just by entering their name, email address and phone number into a form on the site,” but “[a]nyone with a modicum of knowledge about how Web sites work could abuse the LocationSmart demo site to figure out how to conduct mobile number location lookups at will, all without ever having to supply a password or other credentials.” In other words, any person who had some minimal technical skill was able to obtain the real-time locations of other people’s mobile devices, without their knowledge or consent.

One of the most well-known abuses of the Securus’ cell phone tracking services was by the then Mississippi County, Mo. sheriff, Cory Hutcheson. Hutcheson admitted to submitting thousands of requests to obtain location data without legitimate legal authorization; two hundred of which were obtained by uploading fraudulent documents to the Securus platform. His targets included a judge and State Highway Patrol members. He pled guilty to wire fraud and identity theft, and was later sentenced in April 2019 to six months in prison and four months of home confinement.

In response to the controversy, the major carriers announced in June 2018 that they would end location data sharing agreements with third parties. However, less than a year later Vice Motherboard successfully tracked a phone by paying $300 to a bounty hunter, who used the cell phone tracking service Microbilt. Microbilt, like Securus, also relied upon data supplied by a data aggregator – in this case, they purchased access from Zumigo. In its press release [PDF] announcing the fines, the FCC criticized the wireless carriers for not implementing reasonable safeguards to protect customer location data, “even after being made aware of [the unauthorized access by Cory Hutcheson].”

According to the Wall Street Journal, despite the FCC proposing the fines in 2020, there was a four year delay due to “partisan deadlock among the regulator’s four commissioners at the time.” AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon have already stated that they will challenge the FCC’s orders.

Policy Corner

Say Cheese and Jump the Turnstile*

Diane Akerman, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

If not for reporting by Gothamist, a crucial line slipped into the proposed New York State budget might have gone unnoticed by even those active in the digital privacy space. Hidden amidst the increased penalties for poverty fare evasion, a new law states that the MTA “shall not use, or arrange for the use, of biometric identifying technology, including but not limited to facial recognition technology, to enforce rules relating to the payment of fares.” It's not quite the full facial recognition (FRT) ban that advocates have been trying to pass for years, but it demonstrates that there is at least some appetite to consider curtailing the use of this technology.

The use of FRT by law enforcement and civilians have grown exponentially over the last few years, and rarely to good effect - unsurprising, considering its known unreliability and shortfalls. Advocates (including the Digital Forensics Unit) have been working on a slew of bills across the city and state to address the unregulated use of this technology.

S.1609 / A.1891 goes beyond banning just the use of FRT, and also seeks to ban the use of a variety of biometric surveillance tools by law enforcement. The ban is essential to protect New Yorkers from wrongful arrests and prosecutions, particularly as law enforcement tends to obfuscate their use of such technologies [PDF], making them often impossible to challenge in a case.

S.2478 / A.322 seeks to ban the use of the technology by landlords on residential premises, citing ethical and security concerns. FRT is simply too unreliable when it comes to identifying women and men of color to entrust with determining access to one's own home. Landlords also should not have the ability to amass data and use it to potentially discriminate against tenants. There is simply no good reason to subject individuals to surveillance in their own homes.

S.7135 / A.7625 bans the use of biometric surveillance in places of public accommodation. There was quite a bit of backlash when news that James Dolan, the owner of Madison Square Garden and other large venues, was using FRT to ban lawyers from entering MSG. But aside from the minor grudges of a petty billionaire, such racially biased technology should not be used to discriminate against New Yorkers who are just trying to enjoy some entertainment.

S.7944 / A.8853 codifies the existing ban on the use of FRT in public, private, and charter schools in New York. A report and decision [PDF] issued by the New York State Education Department Commissioner outlined the dangers of FRT in school environments.

Countless audits [PDF], reviews, and reports [PDF] have been issued by organizations and government bodies outlining the dangers of the use of FRT. Beyond the well-known and oft-cited reliability issues, these reports almost universally find that FRT is often misused, abused, or has real tangible negative impacts. It is bordering on unconscionable that New York continues to allow its almost entirely unregulated use, and it is time to have a real discussion about banning the scan.

*this not a directive and the author reminds readers that jumping the turnstile is a misdemeanor, with now, increased fines.

Expert Opinions

We’ve invited specialists in digital forensics, surveillance, and technology to share their thoughts on current trends and legal issues. Our guest columnist this month is Sidney Thaxter from the NACDL’s Fourth Amendment Center. He will also be presenting on the topic of automatic license plate readers at Decrypting a Defense: Release the Data on May 21, 2024.

Automatic License Plate Readers

Automatic license plate readers (also known as ALPRs or LPRs) are an old and familiar part of western surveillance culture. They were invented in the United Kingdom in 1976 [PDF] and were first deployed in London in the 90’s as part of the city’s “ring of steel.” At its base the technology behind ALPR networks is fairly simple. It pairs high speed still cameras or video with image processing software that identifies license plates and their location. Once the plate is acquired it can be compared against a database of plates known to be associated with stolen vehicles, wanted persons, suspects, and/or stored for later use.

The caselaw examining ALPRs has generally held that we have no reasonable expectation to privacy in a scan of our license plates. The logic goes that driving is a privilege and the purpose of a license plate is to provide identifying information to law enforcement and others. Therefore, there is “no argument” that motorists seek to keep the information on an outwardly facing set of numbers and letters private. That logic extends to ALPRs because if police and the public can read your plate, so can a computer.

However, in recent years the underpinnings of this caselaw have eroded as both the technology and law have evolved. First, the term automatic license plate reader or license plate reader is no longer accurate. Through machine learning and AI most modern systems recognize vehicle, color, make, and model, as well as distinguishing features like damage or stickers. Thus, the systems are more accurately described as automatic vehicle identifiers (AVIs).

Second, the coverage of the camera networks has grown exponentially as cameras have become more powerful and less expensive. While these cameras used to be expensive and only be placed on or around high value infrastructure and major thoroughfares like bridges or downtown areas, they are now on vehicles, precincts, public/private buildings, highway exits and entrances, and everywhere else one could imagine. Furthermore, the size of the resulting databases has exploded as data storage gets cheaper and cameras proliferate. These databases store not only the license plates of suspects or stolen vehicles (so-called “hotlists”) they run against all of us, even those suspected of no wrongdoing whatsoever. The size of the databases and the ability to retrospectively track everyone’s movements is limited only by the number of cameras and the length of the storage. While some states have laws regulating the length of time this data can be stored and for what purposes it can be used, in many places this has been left up to the law enforcement agencies building the surveillance systems. For example, the NYPD policy [PDF] for AVI data allows retention of all data for five years, and for five years after the death of a criminal suspect, or 90 years after the criminal suspects date of birth as long as there has not been an arrest in the last five years, whichever is shorter. Law enforcement may then use it “in furtherance of a criminal investigation”—a phrase which leaves plenty of room for loose interpretation. Even where there are more robust retention requirements police engage in data sharing with other agencies and private companies that may or may not align with their retention policies.

Finally, the new wave of AVI technology has integrated analytics tools that go far beyond what we previously imagined in this surveillance space. Now companies selling this technology advertise things like predictive travel (predicting where a vehicle will go in the future based on past travel patterns), convoy analysis (identifying vehicles traveling together), associate analysis (identifying vehicles commonly seen in the same area), bulk search analysis (identifying where large numbers of people were over a period of time), and most disturbingly interdiction analysis (identifying “suspicious” travel patterns). These analytics tools can be leveraged against the massive databases tracking all of our movements over years.

It is this last tool—interdiction analysis—that sparked the imagination of the surveillance apparatus at the Westchester Police Department and their Real Time Crime Center. Westchester’s ALPR surveillance network has access to 480 cameras, and it is growing. They scan approximately 16.2 million plates per week and keep those records for two years (or longer when connected to a case). This means that they have at least 1.6 billion vehicle scans in their system at any given time. This network all runs off of the Rekor Scout ALPR platform. The department started using Rekor Scout’s “interdiction analysis” to identify any out of state drivers who visited New York City for an hour or less. If someone was flagged by this feature, someone at the RTCC investigates their Carfax and their criminal history. If they deem that person to be suspicious, they “flag” their vehicle in the ALPR system and alert members of the police department to follow their vehicle and pull them over for a traffic infraction. Then they then have a drug sniffing dog check the car for narcotics or other controlled substances. Despite the massive scale of this program and it’s potential impact on privacy it remained secret until recently.

But this surveillance goes well beyond Westchester PD or Rekor—these analytics tools are offered by most of the major providers like, Flock, Vigilant (now Motorola Solutions), Leonardo ELSAG, etc. They are ever expanding to new “markets” and are now an unavoidable part of travel on open roads in most places in the country.

Law enforcement touts this technology as constitutionally permissible because it merely relies on viewing what is open to the public and designed to provide identifying information. However, earlier caselaw on license plate readers does not address the concerns around long term tracking, mass surveillance, or data analytics used against everyone, regardless of whether they are a suspect in a crime. Those technologies require looking at cases like Jones, Carpenter, and Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle. These cases all reject mechanical application of old precedent to new technologies and recognize a reasonable expectation of freedom from long term warrantless surveillance. Although no court has yet held we have a reasonable expectation to privacy in our license plate scans, cracks in that older precedent are growing, and several cases suggest that as these systems grow they could likely encroach upon the privacy expected out our nation’s founding and violate the supreme court’s ruling in Carpenter. For more information on license plate readers and legal challenges to them visit the Fourth Amendment Center website or email us at 4AC@nacdl.org.

Sidney Thaxter serves as a Senior Litigator for the Fourth Amendment Center at NACDL, which provides the defense bar with resources and litigation support designed to preserve privacy rights in the digital age. Sidney focuses on new and emerging electronic surveillance including: location tracking, communication interception, device searches, government hacking, biometric identification, and data collection.

Upcoming Events

May 8, 2024

Defense Strategies for Getting (and Challenging) Social Media Evidence (NACDL) (Virtual)

May 16, 2024

Technology Innovations and the Law: The Future of Legal Practice in the Age of AI (New York City Bar) (New York, NY)

May 21, 2024

3rd Annual Decrypting a Defense Conference (Digital Forensics Unit) (Queens, NY) (Legal Aid Society Registration) (Non-Legal Aid Society Registration)

June 4-6, 2024

Techno Security East 2024 (Wilmington, NC)

July 12-14, 2024

HOPE XV (Queens, NY)

July 22-25, 2024

2024 HTCIA Global Training Event (Las Vegas, NV)

August 8-11, 2024

DEF CON 32 (Las Vegas, NV)

October 14-15

Artificial Intelligence & Robotics National Institute (ABA) (Santa Clara, CA)

October 19, 2024

BSidesNYC (New York, NY)

Small Bytes

How governments are using facial recognition to crack down on protestors (Rest of World)

Dark Money Is Paying for the Police’s High-Tech Weapons (Jacobin)

NYC Has Tried AI Weapons Scanners Before. The Result: Tons of False Positives (Hell Gate)

Privacy Reformers Turn to Congress as Police Surveillance Expands (New York Focus)

How to Stop Your Data From Being Used to Train AI (Wired)

Artificial intelligence in NY’s courts? Panel will study benefits - and potential risks. (Gothamist)

AI was supposed to make police bodycams better. What happened? (MIT Technology Review

Cops can force suspect to unlock phone with thumbprint, US court rules (Ars Technica)

Taser Company Axon Is Selling AI That Turns Body Cam Audio Into Police Reports (Forbes)

ShotSpotter Keeps Listening for Gunfire After Contracts Expire (Wired)