Doorbell Surveillance, The POST Act, Biometric Surveillance Ban, Digital Forensics Discovery & More

Vol. 3, Issue 11

November 7, 2022

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. In this issue, Joel Schmidt discusses the New York City Police Department’s involvement in Amazon’s Neighbors app. Jerome Greco examines the NYPD Inspector General’s new report on the POST Act. Diane Akerman reviews the current state of biometric privacy legislation. Finally, Allison Young presents the first part of a series on digital forensics discovery.

The Digital Forensics Unit of the Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts and examiners, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of the Legal Aid Society.

In the News

Friendly Neighborhood Surveillance

Joel Schmidt, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

This week, the NYPD announced its participation in Amazon’s controversial Neighbors app. Neighbors is integrated into the Amazon Ring ecosystem. The app enables users to post and receive neighborhood alerts within a five-mile radius. These posts are frequently accompanied by video footage seamlessly shared from Amazon Ring doorbell cameras.

With its new Amazon partnership, the NYPD can now view all posts on the Neighbors app within New York City, including all video posted by users. The NYPD can also view all the poster’s contact information if it is shared in the post. Essentially there is now a police officer in the room in what was previously communication between neighbors. What’s more, the NYPD can now post a “Request for Assistance” seeking Ring doorbell footage or other information to assist in a police investigation. Whenever a user responds with Ring video footage, that user’s street address and email is shared with the NYPD.

The privacy and civil rights group Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (STOP) denounced the partnership with the NYPD, warning it would promote vigilantism, racial profiling, and police violence. “Most New Yorkers would second guess installing these home surveillance tools if they understood how easily these systems could be used against them and their families by police,” said STOP Executive Director Albert Fox Cahn.

Amazon’s Ring program is no stranger to controversy. Users often use racist language or make racists assumptions about individuals depicted in videos. Any user can post a video and describe a person depicted as suspicious. In a 2019 investigation, Vice Media reviewed over 100 Neighbors posts within five miles of its headquarters in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The majority of people reported as suspicious were people of color.

Last year, the Electronic Frontier Foundation reported that the Los Angeles Police Department contacted Ring users seeking recordings of Black Lives Matter protests through a discontinued practice allowing police departments to request video footage via email. This year, it was revealed by Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey that Amazon directly sent the police Ring video footage eleven times without user consent or pursuant to a court order. Amazon tracks an enormous of data through its constellation of products like Ring, Alexa, Kindle, Amazon Music, Prime Video, Audible, and Goodreads, and through its flagship website. Senator Markey recently remarked that “it has become increasingly difficult for the public to move, assemble, and converse in public without being tracked and recorded.”

With the holidays approaching, it may be tempting to gift yourself or a loved one with a Ring camera, but these cameras and the Amazon partnerships with law enforcement may not be as innocuous as they seem.

The NYPD’s Continued Refusal to be Transparent about its Surveillance Technology

Jerome D. Greco, Digital Forensics Supervising Attorney

Late last week, the New York City Department of Investigation’s Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD (OIG) released its highly anticipated inaugural report [PDF] on the NYPD’s compliance with the POST Act.

In July 2020, then Mayor Bill de Blasio signed the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology (POST) Act into law. The law was a watered-down version of the Community Control over Police Surveillance (“CCOPS”) model legislation, versions of which have been passed into law around the country with varying levels of controversy. New York City’s version imposed minimal transparency requirements for the NYPD’s purchase and use of electronic surveillance tools. The law required the NYPD to publish draft Impact and Use Policies for each tool, allow the public to comment on them, and then publish finalized policies. The OIG was then required to publish an annual report, detailing whether the NYPD had complied with the Impact and Use Policies, including whether there were any known or reasonably suspected violations of those policies. OIG was also empowered to make recommendations in its report. The complete details can be found in the final bill [PDF].

On January 11, 2021, the NYPD published thirty-six draft Impact and Use Policies, starting a 45-day countdown for public comments. The draft policies received significant criticisms from many of the groups that had supported the POST Act because the drafts relied on generic boilerplate language, lacked details, and had inaccuracies, among other critiques. The Legal Aid Society submitted three letters during the comment period. The first was a 47-page letter [PDF] on our own behalf. The other two were as members of coalitions, including the G.A.N.G.S. Coalition’s letter and a letter [PDF] with The Bronx Defenders, Center for Constitutional Rights, and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. Additional comments from other groups can be found on the Brennan Center’s page.

Four months after the draft policies were posted, the NYPD published the final versions of the Impact and Use Policies. Not surprising anyone, the policies had few changes, and in some cases were worse than the initial drafts. For example, instead of defining terms like artificial intelligence and machine learning, the NYPD just removed references to them completely. While the policies give some insight into the electronic surveillance tools the NYPD uses, they fall far short of even the low expectations many advocacy groups had. Many POST Act supporters, including myself, never viewed it as a solution or felt it went as far as it should. We understood that it was always meant to be a small step in a bigger fight. The NYPD’s refusal to meet such a low bar solidifies the need to increase the pressure.

The OIG’s report is not perfect. For example, it adopts the NYPD’s incorrect interpretation of what the policies needed to include to address the potential disparate impact on protected groups. However, the report made fifteen recommendations, many of them excellent, including that the NYPD should identify each agency by name that it shares surveillance data with, each surveillance tool should get its own policy and not be grouped together, and the NYPD should create written policies on modifying photos used for facial recognition. The City Council should enact these recommendations into law, if, as expected, the NYPD fails to voluntarily adopt them.

Policy Corner

Biometric Surveillance: To Ban or To Regulate?

Diane Akerman, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

It didn’t take some jurisdictions very long to recognize the dangers of government and law enforcement use of facial recognition software and agree that a ban, even if temporary, was the most immediate and necessary answer. San Francisco was the first major city to ban government use of facial recognition technology, via passage of the Stop Secret Surveillance Ordinance in 2019. Since then, dozens of cities across the country have followed suit, including Boston, Seattle, Pittsburgh, Portland (both the one in Oregon and Maine), and dozens more.

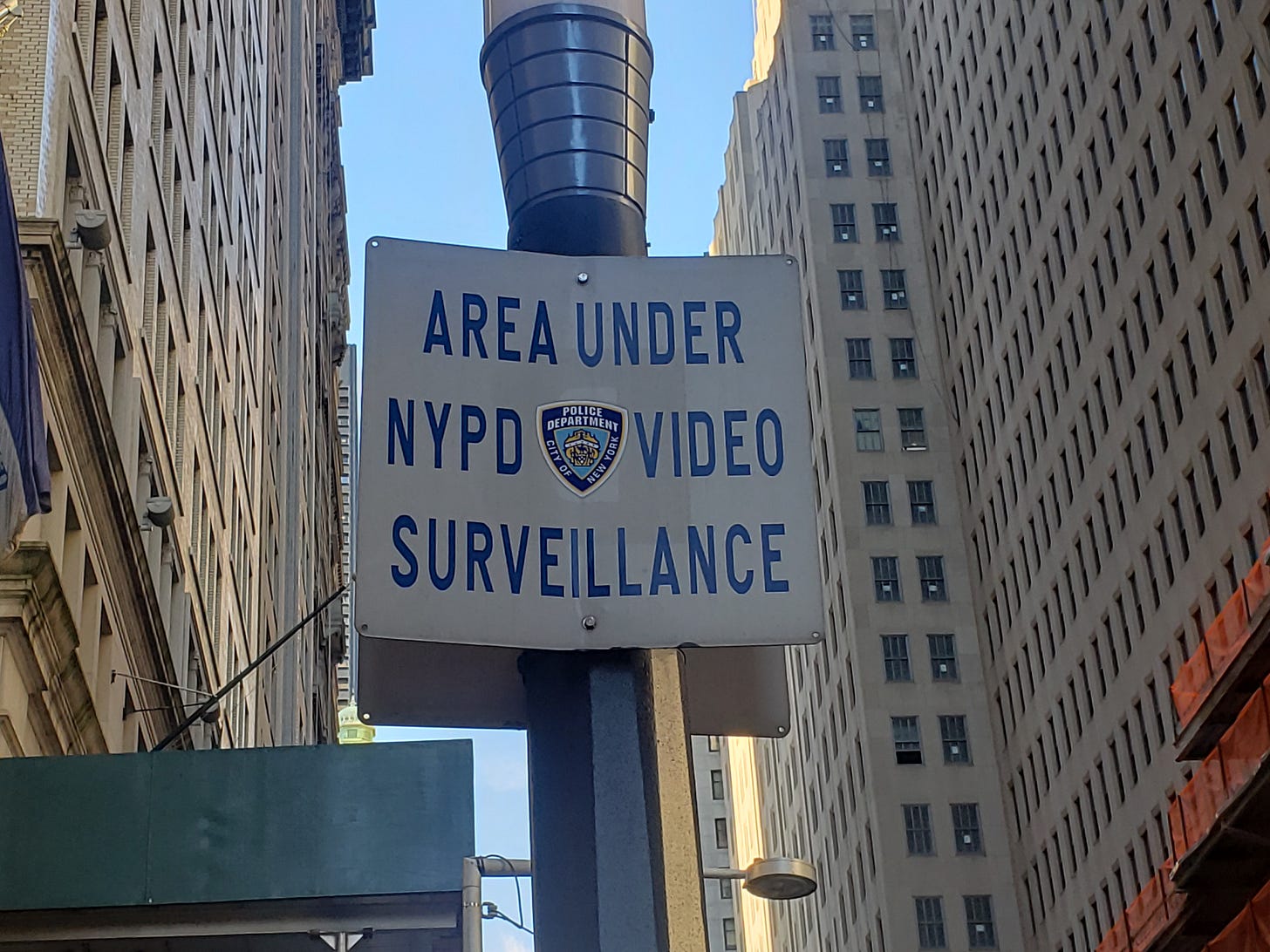

If the idea of biometric scanning and facial recognition still seems like a vague, futuristic threat, think again. It is nearly impossible to walk around New York City and avoid having your face (and other data!) tracked. Don’t believe me? Use this interactive tool created by Amnesty International – plug in any two locations, and it’ll show you how often your face has been tracked.

Following slowly behind other local governments, a Biometrics Ban Bill is currently pending in both the New York State Senate and Assembly. First introduced by Senator Brad Hoylman in the 2019-2020 legislative session, and currently in committee, the Biometrics Ban Bill prohibits not only the use of facial recognition technology, but numerous other forms of biometric surveillance by law enforcement and government agencies.

The bill very broadly defines “biometric information” as “any measurable physiological, biological or behavioral characteristics that are attributable to an individual person, including facial characteristics, fingerprint characteristics, hand characteristics, eye characteristics, vocal characteristics, and any other physical characteristics that can be used, singly or in combination with each other or with other information, to establish individual identity.” It also broadly defines “biometric surveillance,” thereby providing for significant and sweeping protections for New Yorkers against these invasive technologies.

The Bill also establishes a biometric surveillance regulation task force to examine the issues around government use of biometric surveillance, determine whether the use of such technologies should be allowed, and if so, propose a comprehensive set of standards for use of such technology in the future.

The legislation is supported by the Privacy NY Coalition, a coalition of organizational partners working on digital civil rights and surveillance in New York City and State, including The Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit.

Ask An Analyst

The following article is part of a special three-part series on digital forensics discovery in criminal cases. Part One addresses call detail records from wireless phone providers. Parts Two and Three will be included in future Decrypting a Defense Newsletters.

Part 1: Intro and Call Detail Records 📍

Receiving and reviewing discovery can be overwhelming, but even more so when digital evidence is involved. Massive PDFs, proprietary report formats, and unique video codecs are a few issues that may leave you feeling like you need a team of experts to make sense of it all. In fact, you usually do need experts!

The true danger is when digital evidence is received in a format that seems reviewable “as is.” Discovery may include maps depicting the location of your client's phone or printouts of incriminating text message conversations. These items may be skewed to support the prosecution’s proposed timeline of events. They may even have questionable authenticity, such as evidence not properly collected from witnesses or outright fabricated.

Without additional digging (and sometimes additional data), you may not be getting the full picture from your discovery. This is Part 1 in a series detailing digital evidence you might encounter and how a digital forensics analyst or examiner can assist.

Call Detail Records (CDRs)

Records subpoenaed from phone companies like AT&T and T-Mobile typically appear as spreadsheets and/or PDFs that include information about the phone subscriber, the dates and times of their cell phone network usage, and sometimes locations.

Returns will vary in their format, layout, and what data is recorded depending on the dates of records requested, the date of the request itself, and which phone company maintains this information. These records are kept for billing and engineering purposes – not specifically for legal use.

Every so often I see a well-meaning person try to map and interpret cell site location records (CSLRs) without being aware of best practices. Those unfamiliar with these returns do not consider the difference between GPS coordinates that document a phone’s location and cell tower coordinates that indicate the known location of a cell site. Also, it's not uncommon for the times in a records return to be kept in multiple time zones – improperly mapped records could be inaccurate by several hours.

Returns may be missing crucial context, like other cell towers in the area that were not used by the phone. A forensic examiner or analyst will be better prepared to analyze this data than your average attorney or paralegal.

Takeaways:

Locations in call detail records or cell site location reports are NOT an individual’s location

Records are prepared with techno-jargon, documentation, and varying time zones that you need an expert to properly interpret

Records may be missing context or additional data necessary to complete analysis

The accuracy of some records vary depending on their intended use because they are kept for billing and engineering purposes, not for forensic analysis

Be sure to read Part 2 in December’s Newsletter!

Allison Young, Digital Forensics Analyst

Upcoming Events

November 8, 2022

Lawyering After Dobbs: Securing Care and Digital Privacy (The Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University) (Virtual)

November 10, 2022

Developing Defense Strategies After Dobbs: Public Defense Summit (NACDL) (Virtual)

November 18, 2022

Race Ex Machina: Confronting the Racialized Role of Technology in the Criminal Justice System (Berkeley Center for Law & Technology/Berkeley Technology Law Journal/Coalition of Minorities in Technology Law) (Virtual)

November 21, 2022

The Role and Influence of Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace (NYC Bar) (Virtual)

December 1, 2022

Cybersecurity for Lawyers: Is Your Firm Safe From Cyber Attacks? (NYSBA) (Virtual)

March 11-18, 2023

Open Data Week 2023 (Various Locations in NYC)

April 17-19, 2023

Magnet User Summit (Magnet Forensics) (Nashville, TN)

April 27-29, 2023

16th Annual Forensic Science & The Law Seminar (NACDL) (Las Vegas, NV)

Small Bytes

How Mobile Phones Became a Privacy Battleground - and How to Protect Yourself (New York Times)

When School Superintendents Market Surveillance Cameras (Vice)

Evaluating the Growing Movement to Stop ShotSpotter (Tech Policy Press)

How expanding web of license plate readers could be ‘weaponized’ against abortion (The Guardian)

Police Are Using DNA to Generate 3D Images of Suspects They’ve Never Seen (Vice)

Meta’s New Quest Pro Headset Harvests Personal Data Right Off Your Face (Wired)

A bias bounty for AI will help to catch unfair algorithms faster (MIT Technology Review)

Strava’s Jogging Data Illustrates the Persistence of Gentrification (Gizmodo)