AI and the Practice of Law, Unbanked Surveillance, Digital Civil Rights, Discovery Review (Part IV), & More

Vol. 4, Issue 2

February 6, 2023

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. In this issue, Jerome Greco discusses artificial intelligence in the practice of law. Joel Schmidt reviews the surveillance of banking records. Diane Akerman discusses a state-wide campaign to make New York a Surveillance Sanctuary State. Allison Young presents video issues in the fourth part of a series on digital forensics discovery.

The Digital Forensics Unit of the Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts and examiners, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of the Legal Aid Society.

In the News

AI and the Practice of Law

Jerome D. Greco, Digital Forensics Supervising Attorney

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) continues to grow and infiltrate every facet of life, so it should not surprise lawyers that the legal industry is not immune. With the growth of AI comes the growing list of controversies it creates, leading to attempts to regulate and limit its uses, including the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights from The White House and the AI Risk Management Framework by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), among many others. Entire books can and have been written on even small issues involving AI. Here, I will very briefly discuss two of the more attention receiving technologies as they relate to the practice of law: ChatGPT and DoNotPay.

The use of AI in the practice of law is not new. Algorithms, machine-learning, and AI overall have been used in eDiscovery and other areas for many years. However, they are often viewed as tools to help diminish the workload, rather than to outright replace the need for the lawyer. Despite sensationalistic headlines, the new crop of AI powered services are also tools that can aid attorneys and not completely replace us.

ChatGPT is “a conversational AI language model developed by OpenAI. It was trained on a massive dataset of text data from the internet, allowing it to generate human-like responses to a wide range of questions and prompts.” That was the correct answer provided to me by ChatGPT when I asked it “What is ChatGPT?” Although some have touted the end of law school exams and the death of the lawyer, ChatGPT is not currently able to achieve that. For example, in one study it passed some parts of a bar exam, but it has also failed other sections. In another study, it passed some law school exams with mediocre grades. ChatGPT does not always provide the correct answer. It sometimes gives no citations for its work, or even worse, it sometimes cites to incorrect or non-existent sources.

DoNotPay describes itself as “the world’s first robot lawyer.” It recently received mixed attention when its CEO, Joshua Browder, claimed that its new AI program would advise a real defendant in a real traffic court proceeding in real-time. Numerous criticisms immediately flooded the internet, including that it would be the unauthorized practice of law, the recording of the proceeding would violate a court’s rules (especially when done surreptitiously), and it would be using indigent people as an experiment, among others. It did not take long for Browder to back down, but he has never revealed the intended defendant, the proceeding, or the location. He also has failed to address other questions and criticisms. It leaves one to wonder if it all was a publicity stunt. Since the announcement, more questions about the CEO and DoNotPay have arisen, even calling into question whether their tools are AI-driven.

In the future, ChatGPT or a similar tool may become advanced enough to replace the need for a lawyer, but it is not there yet. In the meantime, it can be used as a starting point for research, or even creating a framework for drafting. Just as with its AI predecessors in the law, attorneys are still ethically and legally responsible for any results they rely upon or adopt. Blaming the AI is unlikely to be an acceptable excuse for any incorrect, missing, or fabricated information. Approach AI as you would a dog on the street; resist the urge to immediately embrace it and proceed with caution. It may be friendly, but it could still bite you.

Unbanked Surveillance

Joel Schmidt, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

If you live or work in New York City you may be familiar with a New York City law requiring all food and retail establishments in the city to accept cash as a form of payment. Almost ten percent of New Yorkers are “unbanked,” meaning they don’t have access to a bank account and are incapable of making digital transactions. Stores that refuse to accept cash impose a burden on already marginalized communities, and are discriminatory against communities of color. When businesses flout the law, the city can crack down.

It has now been revealed that the unbanked in New York City and elsewhere are being discriminated against in a more insidious way, in the form of a surveillance tax. The Wall Street Journal and Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon report that over 600 law enforcement agencies have unfettered direct access, without any court oversight, to over 150 million money transfer transaction records exceeding $500 between anywhere in the United States and twenty countries and various US states, including [PDF] many transactions in New York. The countries listed include Mexico, China, Colombia and other countries with significant immigrant populations in New York City.

Western Union, MoneyGram, and other popular money transfer companies all send a significant amount of their transaction data to a little known nonprofit set up by the Arizona Attorney’s General’s office called Transaction Record Analysis Center, or TRAC. Customers of money transfer companies are “disproportionately [PDF] [from] low income, minority, and immigrant communities,” many of whom are unbanked.

The data is believed to include the names of the sender, the names of the recipient, and the transaction amount. TRAC’s director unabashedly described the database as “a law enforcement investigative tool.” Profiling is not just possible but seemingly encouraged. Internal records reveal a slideshow prepared by a TRAC investigator showcasing the ability to scan bulk transaction records for categories such as “Middle Eastern/Arabic names.”

Money transfer customers are not informed that their transaction data may be submitted to TRAC, or that banking records have more stringent requirements requiring the government to obtain records by way of a search warrant or subpoena.

Agencies with access to the data include the New York City Police Department and the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office.

Senator Wyden is leading an investigation into TRAC and has denounced its practices. TRAC allows the government to “serve itself an all-you-can-eat buffet of Americans’ personal financial data while bypassing the normal protections for Americans’ privacy,” he told the Wall Street Journal. Indeed, the Arizona Attorney General’s Office made no bones of the fact that it exploits court decisions and it claims that courts “have held that customers using money transmitter businesses do not have the same expectation of privacy as traditional banking customers.”

But, as the ACLU stated “People who use money transfer systems are often immigrants, poor people, people of color denied traditional banking. One set of rights for people who have more money and access banks and less rights for those who can’t get a traditional bank account because they have bad credit score.”

Senator Wyden is urging [PDF] the Department of Justice Inspector General to investigate the federal agencies who have used their subpoena power to acquire bulk records submitted to TRAC.

Frequently, to be poor in the United States is to surrender fundamental rights, and that is unacceptable.

Policy Corner

Fighting For Digital Civil Rights

Diane Akerman, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

The battle for privacy civil rights is not only waged in courtrooms with lawyers debating the finer points of how the two-hundred-year-old fourth amendment applies to technology only Gene Roddenberry had the genius to foresee. Where the courts are slow to act, the legislature must move. Enter The Blueprint to End Surveillance, a package of ten bills aimed at making New York a Surveillance Sanctuary State.

Our privacy is constantly diminished by the unavoidable digital footprint we all create by simply existing in the modern world. Even the savviest among us have no choice but to store data with third parties, who are more incentivized to mishandle and profit off of it, than protect it. Meanwhile the constantly expanding surveillance state encroaches on what little privacy individuals maintain in their own bodies and the physical spaces they inhabit.

Rather than insist on personal responsibility, or telling people to just “opt-out,” greater scrutiny and regulations should be directed at those who store our data. Government use of technology must be transparent, and there must be mechanisms for oversight. In some cases, the technology is simply too dangerous and must be banned outright.

Take facial recognition technology. It is biased, it is racist, it results in wrongful arrests and convictions. Proponents of the technology insist it is an objective algorithm, but it’s not. It’s a tool used by people – people who choose where and how to use it. Ultimately a person – not the algorithm – selects the “match” making facial recognition doubly problematic – suffering from the problem of both faulty algorithms and human identification.

The disparate impact of data sharing also cannot be overstated. There is no warrant necessary to get information from an EBT card, sign ins to the NYC shelter system, or even an entire history of MetroCard swipes. People relying on these benefits to survive have no choice but to give up a certain amount of privacy.

Among the bills in the package are the Biometric Ban Bill, which would ban government use of Facial Recognition, a ban on digital dragnets known as Geofence Warrants, and a ban on continued use of “rogue” and unofficial DNA databases by law enforcement. Other bills seek to limit data sharing – prohibiting OMNY from sharing rider data with law enforcement, and a bill prohibiting New York state and local agencies from disclosing data to or in any way colluding with ICE.

The package is the work of a joint coalition of digital privacy rights advocates, the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, and the DNA and Digital Forensics Units at The Legal Aid Society. More information about the package can be found here.

Ask an Analyst

Part 4: Video... and More Video 📹

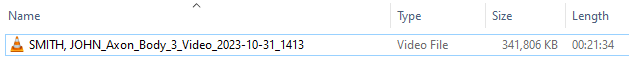

Thanks for reading this month’s overview of digital forensic discovery types, which covers DVR video and body worn camera (BWC) video. DVR and BWC discovery share common issues that affect video evidence, but have their own distinct characteristics to consider as well.

DVR Video Exports

Video files exported from a DVR system can be provided in several formats, as DVR systems use their own proprietary players and file types. While videos may play with VLC Media Player or an included program, they might play back at the wrong speed or lower quality. These issues can be corrected using a forensic video analysis tool.

Our Unit has received video files labeled as DVR exports that we then determine are likely recordings of a video screen, missing crucial metadata for confirming exact dates and times of events. We have also received lower quality files than what may be available to the prosecution. Working with the highest quality file ensures that we have enough information and detail to perform video enhancements, enlarge or clarify text, and ultimately testify about our analysis work.

Forensic experts can correct aspect ratios (the culprit behind “stretched” looking video), add annotations, extract stills, or prepare compilation clips as needed.

Takeaways:

There is little standardization in DVR systems – proprietary software may prevent playing surveillance video. If the video plays, the quality may be reduced or missing data

DVR footage can be improperly saved, screen-recorded, or recorded using a secondary camera, reducing quality or missing data

An expert can use specialized software to play video more accurately and enhance colors, contrast, and playback speed for easier review

Body Worn Camera (BWC) Footage

Body worn camera footage may suffer from the same quality issues as DVR exports during the discovery process. In addition to identifying these issues, a digital forensics expert can clarify BWC footage to play multiple perspectives side by side, slow down the playback speed, and stabilize a moving area of interest. An expert can add an adjusted timestamp for the local time zone (as opposed to UTC, which is the default shown in many BWC videos).

Have you ever noticed that NYPD BWC video includes about 1 minute of video without audio? This is because the cameras are always buffering, recording video without audio. The last 1 minute of video is constantly overwritten until an officer starts recording. The first 1 minute of video captures an event before the officer initiates their own recording of the event.

Takeaways:

Body worn camera footage may be difficult to view due to rapid movement or shaking

Not all colors or quality may be displayed using the default video player

An expert can prepare side-by-side synced BWC compilations to show multiple angles of an encounter at once

Allison Young, Digital Forensics Analyst

Upcoming Events

February 8, 2023

Simple Legal Tech Security Measures Every Law Office Should Take (NYSBA) (Virtual)

February 21, 2023-March 2, 2023

Magnet Virtual Summit (Magnet Forensics) (Virtual)

March 11-18, 2023

Open Data Week 2023 (Various Locations in NYC)

March 20, 2023

Meredith Broussard: Bias Is More than a Glitch (NYPL) (New York, NY & Virtual)

MozFest (Mozilla) (Virtual)

April 17-19, 2023

Magnet User Summit (Magnet Forensics) (Nashville, TN)

April 22, 2023

BSidesNYC (New York, NY)

April 27-29, 2023

16th Annual Forensic Science & The Law Seminar (NACDL) (Las Vegas, NV)

June 5-8, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference East (Wilmington, NC)

August 10-13, 2023

DEF CON 31 (Las Vegas, Nevada)

September 11-13, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference West (Pasadena, CA)

Small Bytes

The Slow Death of Surveillance Capitalism Has Begun (Wired)

Conservative group targets migrant cell phone date at NGOs, raising privacy concerns (Texas Public Radio)

Researchers Could Track the GPS Location of All of California’s New Digital License Plates (Vice)

The FBI Won’t Say Whether It Hacked Dark Web ISIS Site (Vice)

Google Keyword-Search Warrants Questioned by Colorado Lawyers (Bloomberg)

The State Police Are Watching Your Social Media (New York Focus)

Lawyers Barred by Madison Square Garden Found a Way Back In (New York Times)

Confidential document reveals key human role in gunshot tech (AP)

Hochul Wants More Police Surveillance. Legislators Want Boundaries. (New York Focus)