ALPR Lawsuit, Video Authentication, NYS Commission on Forensic Science, Protester Surveillance & More

Vol. 5, Issue 11

November 4, 2024

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. This month, Shane Ferro reviews a lawsuit against a Virginia police department’s use of automated license plate readers. Allison Young examines video authentication in a post-generative world. Lisa Montanez discusses the passage of NY State Senate Bill 9672 and what it means for forensic oversight. Finally, Jerome Greco explains how protesters can protect themselves from surveillance.

The Digital Forensics Unit of The Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal Defense, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of The Legal Aid Society.

Job Postings

The Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit is growing. For over a decade, we have used technology to advocate for our clients in courtrooms across New York City and have fought against government surveillance and the erosion of digital privacy rights. As the the use of electronic evidence has grown, so has the need for our work. As a result, we have recently posted openings for two new staff attorney positions. If you are interested in working with us on digital forensics and electronic surveillance related issues, and you meet the required qualifications, please apply.

Staff Attorney, Digital Forensics Unit (applications close at 3:00pm EST on November 19, 2024)

Staff Attorney, Central – Digital Forensics Unit (applications close at 3:00pm EST on December 16, 2024)

In the News

Fourth Amendment Lawyers Flock to the Fourth Circuit

Shane Ferro, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

On October 21, the Institute for Justice (IJ) sued the City of Norfolk, Virginia, over its police department’s use of Flock automated license plate readers (ALPRs). The lawsuit asserts that police having unfettered access to a database of license plate scans not only in the city of Norfolk, but throughout U.S. cities that use Flock, violates the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments. (Complaint is here [PDF].)

The plaintiffs are seeking to enjoin Norfolk PD from using Flock, requesting the court to order Flock to delete all images and data generated by Flock cameras, and asking the judge to rule that the police need a warrant to access Flock’s data, among other requests.

According to the lawsuit, Flock operates 172 cameras in Norfolk (pop. 238,000), which are constantly reading and ingesting the license plate information of every car that passes each camera. The police department requires that officers use this system, and they have total access to search the license plate database, both in Norfolk and in Flock’s centralized database of more than 5,000 communities with Flock cameras, without a warrant and without probable cause. According to the complaint, the Norfolk Police Chief has previously said the Flock cameras “create[] a nice curtain of technology” around the city.

This is the central claim, from paragraph 9 of the complaint:

“The City is gathering information about everyone who drives past any of its 172 cameras to facilitate investigating crimes. In doing so, it violates the longstanding societal expectation that people’s movements and associations over an extended period are their business alone. And because the City does all of this without a warrant—instead letting individual officers decide for themselves when and how to access an unprecedented catalogue of every person’s movements throughout Norfolk and beyond—the City’s searches are unreasonable.”

This lawsuit attempts to build on prior Fourth Circuit precedent. The Fourth Circuit struck down the city of Baltimore’s aerial surveillance program in Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle v. Baltimore Police Department, 2 F.4th 330 (2021) (en banq). According to IJ, the Flock automated license plate readers go far beyond the surveillance in Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, as the dragnet surveillance in that case was only able to articulate “blurred dots, or blobs” from the air. ALPRs are literally on-the-ground and able to capture images with such specificity that they can articulate individual letters on a license plate. If you’ve ever seen ALPR discovery as an attorney, you know that the cameras can be quite good, and may capture an alarming level of detail with each passage of a car past a camera.

Robert Frommer, one of the IJ lawyers who filed the complaint, told 404 Media that the Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle precedent is one of the main reasons they decided to file suit in Norfolk, even though they thought they had standing in any one of the 5,000 places Flock operates.

There’s also a recent decision [PDF] from a trial-level state court in Norfolk granting suppression in a robbery case in which the key holding is that the Norfolk PD accessing the Flock database was search.

More Need for Video Authentication in Society’s Deepfake Era

Allison Young, Digital Forensics Analyst

A large front of manipulated video, photographic, and audio content is creating problems in public trust and personal safety. This month, tech companies announced new mitigations for misleading deepfakes, including improved video authentication and tools to flag fake content. Deepfake videos will find their way into legal discovery as generative capabilities leech into consumer phones, AI use in crime increases, and states push hundreds of AI-related bills, some of which include criminal sanctions.

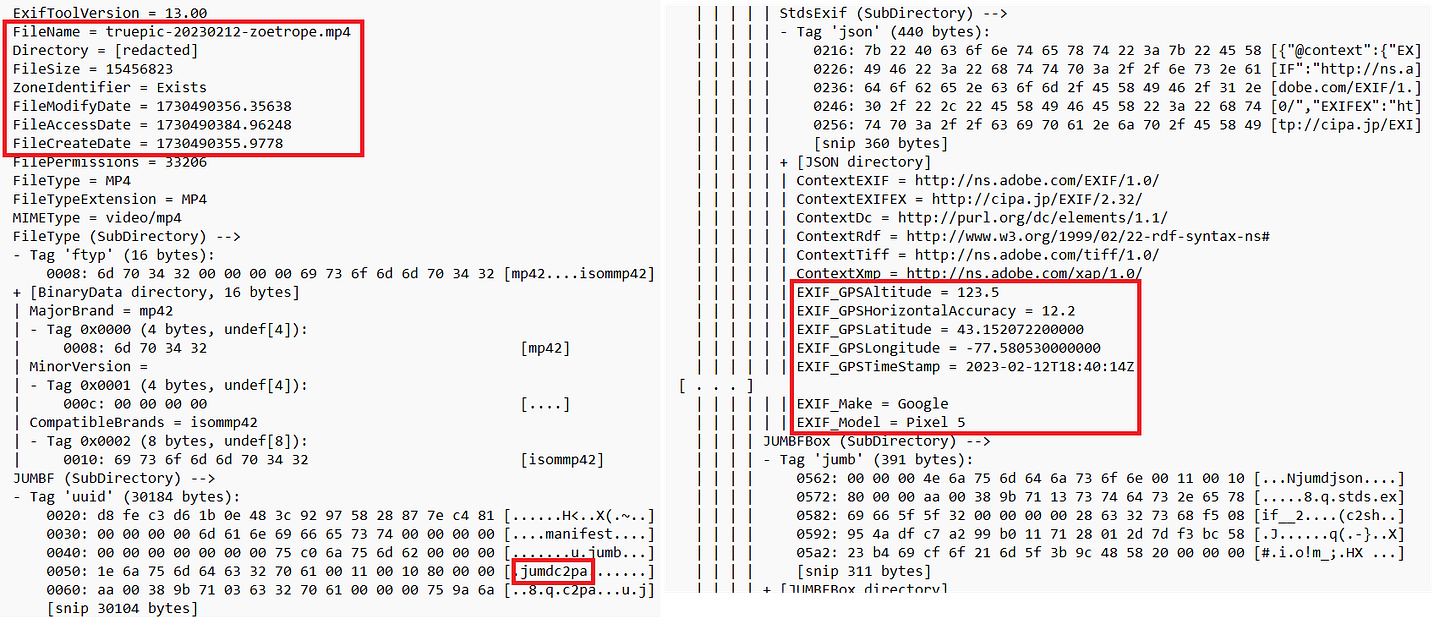

When handling digital video evidence, we already have many methods at our disposal to evaluate authenticity. We can gather facts showing that video was collected properly from a surveillance system or directly from a device (for instance, a phone) that was used to capture a video. Visual inconsistencies, like the ones caught in the Karen Read murder trial, can tip attorneys off to the need to question how evidence was handled between the camera and the courtroom. We can review video metadata to identify issues, such as abnormal timestamps or embedded location data that is not consistent with what the video is alleged to depict. There is also increasing awareness of methods to analyze video file structure with tools like MedEx, which maintains a dataset of digital video file characteristics that suggest edits, re-uploads, or likely status as a “camera original.”

Still, deepfakes create novel issues. A disinformation group fabricated a video of an individual stating that he was Matthew Metro and that he was molested by Vice Presidential candidate Tim Walz. It reached millions despite the real Matthew Metro coming forward to discount it. It also was likely not a true “deepfake,” but because social media has been so saturated with machine-dreamed content, it feeds suspicion of anything that we see. Celebrities and politicians aren’t the only targets, as more people discover that their likenesses have been stolen to promote brands or create non-consensual pornographic material. Damage is done as harmful content is viewed, whether by what the video shows or by a seeding distrust in any digital video that exists.

Companies are trying to regain viewer trust with traditional methods, like content moderation, and new approaches. YouTube announced support for C2PA Content Credentials, displaying them when available beneath videos uploaded to their platform. C2PA is an authentication standard that binds a watermark to digital media that includes information about its source and creation methods. Attempts to edit the video without accurately updating its C2PA “provenance” should break the credentials. Newer smartphones with Qualcomm chips may support it, as well as some new models of cameras. Changes to content in tools like Adobe Photoshop will also be tracked in C2PA information.

Unfortunately, the standard is not backwards compatible with every tool or camera. C2PA credentials would aid legal professionals in dealing with future video content in their cases, but the watermarks will inevitably be absent from crucial sources like business surveillance systems, where it's not surprising to see DVRs that are several years old.

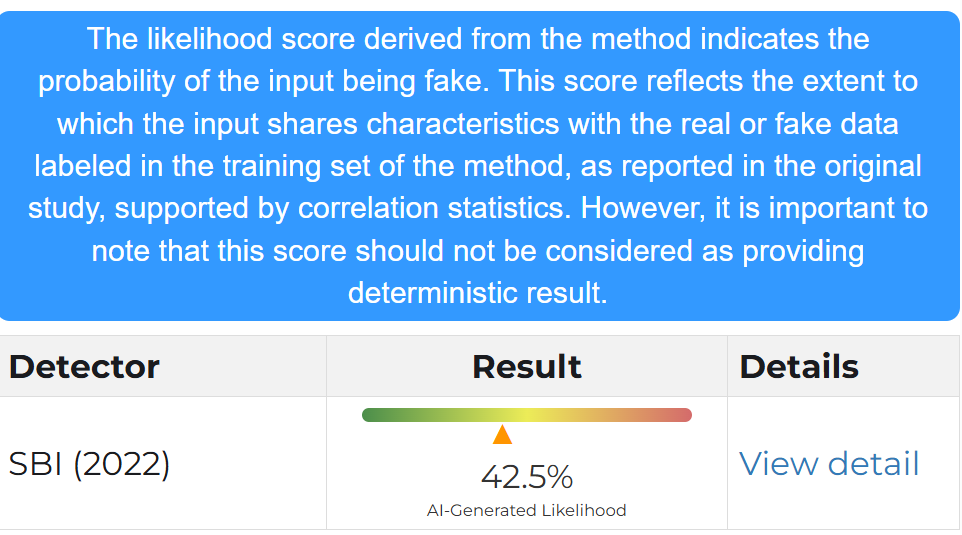

For images without C2PA, there are several tools to identify AI manipulation. McAfee offers one such tool (also powered by AI) and it was announced this month that they were partnering with Yahoo News to use it on their content. You can access your own collection of AI-detection methods, like a free “DeepFake-oMeter” tool by the UB Media Forensics Lab or the many gathered on this Github page. However, existing digital forensics practices can and should still be applied when evaluating whether questioned video is authentic, accurate, and relevant – including deepfakes.

In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court stated “We are happy to allow the videotape to speak for itself” in Scott v. Harris, 550 U.S. 372 (2007). This opinion is no match for the blurred line between reality and generative reality we are seeing today, but digital forensic analysis and new technologies will help with video evidence issues.

Policy Corner

Reforms to the NYS Commission on Forensic Science

Lisa Montanez, Digital Forensics Paralegal II

Earlier this year, the NY State Senate passed legislation S9672, a bill which reforms the NY State Commission on Forensic Science. Significant amendments to the executive law have opened the door to implementing more oversight of crime laboratories, particularly when it comes to incorporating review and input from external scientific experts and academic faculty members. For many years, forensic science has been able operate in a vacuum due to practitioners limiting external scientists from weighing in on whether the practices within these labs meet standards and have scientific merit. The legislative changes hold the field accountable to an objective group of experts, rather than relying on lab accreditation by a private entity or the hope that practitioners are objective and competent enough to monitor themselves (recent scandals indicate they are not).

Determining whether a laboratory is compliant with scientific standards is complex. It is one reason why several industries rely on private companies or non-profit organizations to provide accreditation as a way to prove to their stakeholders a lab is following best practices. However, even the government knows this is a bare minimum checkpoint, and that follow up audits by an entity with regulatory enforcement authority is required. For example, the agricultural and pharmaceutical industries are subjected to lengthy government audits where their processes are reviewed for compliance against state and/or federal regulations. Presently, there is no regulatory body that is responsible to ensure forensic testing laboratories are following best practices; they can look to an organization like the Organization of Scientific Area Committees for Forensic Science (OSAC), but they can only provide guidance documents. This is where forensic boards and commissions, created through state legislation, can fill the gap.

Forensic boards and commissions serve as a watchdog over their state’s forensic laboratories. They can assess whether a lab is following best practices, such as requiring the submission of audit reports and action plans in response to observed deficiencies. Currently, legislation has been passed at the state level to create eighteen boards and commissions. The NY State Commission on Forensic Science was established by Article 49-B of the executive law, and its primary duty was initially described in Section 995-b as a group responsible to “develop minimum standards and a program of accreditation for all forensic laboratories in New York State.” Prior to the reforms, Section 995-a required a significant portion of commission members be pulled from law enforcement agencies and forensics laboratories (the language used to describe the criteria for membership included a “director of a forensic laboratory located in NY state,” “the chair of the NY state crime laboratory advisory committee,” the “director of the office of forensic services within the division of criminal justice services,” “a representative of a law enforcement agency,” and “a representative of prosecution services”). The new commission structure supports a more objective review of the work in forensics labs since the criteria now incorporates scientific experts from academia, including ones with an expertise in bioethics, statistics, clinical lab science, and cognitive bias. In addition, there are now three permanent advisory committees to the commission: a scientific advisory committee, a forensic analyst license advisory committee, and a social justice, ethics, and equity assessment committee. The inclusion of a social justice committee is a significant step towards hindering the acceptance of new methodologies before considering whether they are harmful to equity, and an acknowledgement that faulty forensics has the greatest impact on Black and brown communities, a group which continues to make up the largest percentage of our prison population. This committee is tasked with making recommendations to the commission to reduce racial disparities; among its powers is to “assess built in biases in algorithms and the disparate impact of technologies.”

Additional reforms that support a more objective review of forensic labs includes requiring that one expert work outside of New York, academic faculty members may not have prior experience working for law enforcement/prosecutorial entities, and that a motion for the secretive “executive session” must provide enough detail for the public to evaluate whether it is appropriate. This is an effort at ensuring the commission remains transparent and limits the opportunities to abuse the use of an “executive session” to hide policy matters and systemic issues from the public.

What do the reforms to the NYS Commission on Forensic Science mean for oversight in digital forensics? S9672 does not apply to digital evidence (“...the use of mobile forensic digital tools to extract data from cellphones and computers by a police agency shall not be subject to the provisions of this article”). However, the passage of this legislation has the potential to influence advocacy efforts for digital forensics oversight. Unfortunately, how to implement oversight within this field remains contentious and difficult. This is largely due to the rate at which digital forensics evolves in comparison to the physical and biological scientific disciplines. Nonetheless, digital forensic professionals still advocate for the development and harmonization of standards. The OSAC’s Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence (SWGDE) have to the best of their abilities established a set of guidance documents for practitioners to reference.

Hopefully, the passage of this legislation mean there is an increase in public support for transparency and oversight in forensic science. There’s numerous scandals that have emerged out of crime labs in the past decade that indicate courts and juries shouldn’t accept this kind of evidence without scrutiny. Recent stories, such as the ongoing investigation into the Colorado Bureau of Investigation DNA analyst and the NYC Office of the Chief Medical Examiner DNA contamination scandal and misconduct probe, are insight into the problems that persist in forensic labs. It would be incumbent on the field to welcome oversight efforts. Be better forensics. People’s lives and freedom depend on it.

Ask an Attorney

Do you have a question about digital forensics or electronic surveillance? Please send it to AskDFU@legal-aid.org and we may feature it in an upcoming issue of our newsletter. No identifying information will be used without your permission.

Q: How can I protect myself from surveillance while protesting?

A. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the issue of surveillance of protesters and activists. When members of the Digital Forensics Unit present digital security and know your rights trainings, we do our best to tailor them to the circumstances of the group. However, there are factors that everyone should consider and some general pieces of advice that will apply to most in many situations. This column should not be considered a complete answer. My goal in answering here is to get readers thinking the way they need to in these circumstances and provide basic advice and resources.

First, you want to perform a threat model assessment (also known as a risk assessment). The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has put together a helpful one-pager on the topic. The idea is that not every person and not every situation will have the same risks or require the same precautions. Additionally, as with all things, especially as they relate to the criminal legal system, privileges and personal circumstances matter.

Here are some of the questions you should consider when preparing to protect yourself and others from surveillance. If you are participating in a group action it would be best to discuss these topics with the other members of your group, if possible.

What do you want to protect?

You may want to protect your identity because you fear arrest. Or you may want to protect yourself more broadly from being doxed. Similarly, you may want to prevent someone from impersonating you to infiltrate a group you are organizing with. Identifying your concerns is a helpful first step.

Who are you protecting it from?

Determine who your potential adversaries are or will be. It could be law enforcement, people on the other side of the political spectrum, or even people who under other circumstances you may not view as an adversary (e.g. coworkers, fellow students, neighbors). Anyone who poses a threat to what you are seeking to protect may be an adversary.

How likely will it need to be protected?

Not all information is at the same risk. For example, a private actor may be able to identify your social media accounts and use that information to dox you and harass people connected to you. However, short of successfully hacking your account, they won’t be able to obtain private data such as private messages, but law enforcement may be able to.

What happens if you are unsuccessful at protecting it?

Identify the consequences if you are unable to protect the data or information. Will it lead to your arrest or losing your job? Will your school suspend you? Will your home no longer be safe or your physical security be at risk?

What are the threats that others in your action or aligned with your goals face?

People will have different risks, which is one of the reasons it is important to have a group threat model assessment, in addition to an individual evaluation. For example, you may not be concerned about being identified, so you post pictures of yourself and others at the action. But do the other people in those pictures have reason to fear the posting of their likenesses on social media, and are they aware that (1) you took the pictures and (2) that you intend to post them publicly?

What measures can you take to eliminate or mitigate the identified risks?

Identify potential options in response to each threat. For example, you concerned about your location being tracked. Can you leave your phone at home?

How feasible are those measures?

Some options cost money or may put someone in a position they are not willing to accept. For example, not carrying a cell phone may work for some, but for others they may need to be reachable by their children, sick family member, etc.

As discussed above, individual circumstances guide decisions and nothing is foolproof, but below are some general tips that are useful in many situations for most people.

Leave all electronic devices at home. If that is not possible, bring only what you absolutely need to, and, if possible, use a clean device specifically for this purpose (e.g. burner device).

Disable face/fingerprint unlock. Use a 6+ alphanumeric character password.

Turn off GPS, NFC, Bluetooth, WiFi, and any location services.

Use trusted end-to-end encrypted messaging apps to communicate, like Signal, with the disappearing messages feature on.

Lock down your social media privacy settings. Don’t tag or post identifiable images of people without their permission.

While not a perfect solution against facial recognition, wearing sunglasses, a face mask, and a hat, will make it more difficult to be identified.

Avoid wearing unique or easily identifiable clothing or displaying tattoos.

Follow standard advice on police interactions.

a. You have the right to remain silent. If you choose to talk to the police, it can be used against you. Do not tell the police anything except your name, address, and date of birth.

b. If you’re arrested, ask for a lawyer immediately.

c. Do not consent to any searches, including of your devices. Do not unlock your devices for police.

Thankfully, there are multiple resources available for further help.

The Legal Aid Society’s What You Need to Know About Your Rights as a Protester and Your Rights, Your Power

Freedom of the Press Foundation’s Digital Security Education

Digital Defense Fund’s Resources

Surveillance Technology Oversight Project’s Protest Surveillance: Protect Yourself

Jerome D. Greco, Digital Forensics Director

Upcoming Events

November 5, 2024

Artificial Intelligence in Law Practice 2024 (PLI) (New York, NY or Virtual)

November 15, 2024

New Perspectives: Using AI to Expand Your Horizons and Reduce Personal Bias (NYSBA) (Virtual)

November 18, 2024

The Color of Surveillance: Surveillance/Resistance (Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology) (Washington, DC)

November 18-20, 2024

D4BL III (Data for Black Lives) (Miami, FL)

December 5, 2024

Policing Pregnancy: The Impact of Data and Surveillance on Reproductive Healthcare (NACDL) (Washington, DC)

December 5-6, 2024

Questioning Forensics: To Err is Human, To Do Science is… Still Human (Legal Aid Society) (New York, NY)

December 11, 2024

Cyber Security, Ethics and the Current State of Data Privacy (NYS Academy of Trial Lawyers) (Virtual)

December 18, 2024

AI and Legal Services: The Present and Future (PLI) (Virtual)

January 30-31, 2025

NAPD Virtual Tech Expo (National Association for Public Defense) (Virtual)

February 17-22, 2025

AAFS Annual Conference - Technology: A Tool for Transformation or Tyranny? (American Academy of Forensic Sciences) (Baltimore, MD)

February 24-March 3, 2025

SANS OSINT Summit & Training 2025 (SANS) (Arlington, VA or Virtual)

March 17-19, 2025

Magnet User Summit (Magnet Forensics) (Nashville, TN)

March 24-27, 2025

Legalweek New York (ALM) (New York, NY)

April 24-26, 2025

2025 Forensic Science & Technology Seminar (NACDL) (Las Vegas, NV)

Small Bytes

White House issues guidance for purchasing AI tools to US agencies (FedScoop)

License Plate Readers Are Creating a US-Wide Database of More Than Just Cars (Wired)

Police seldom disclose use of facial recognition despite false arrests (Washington Post)

Can police search your phone? Here are your legal rights. (Washington Post)

Nashville, Tenn., police want private businesses to share surveillance video feeds (StateScoop)

Can You Turn Off Big Tech's A.I. Tools? Sometimes, and Here's How. (New York Times)

Inside Apple’s Secretive Global Police Summit (Forbes)

NYC Evolv weapons scanner pilot in subways: No guns, 12 knives, unanswered questions (NY Daily News)

NYPD’s subway gun scanners fail to meet expectations (PIX11)

Google, Microsoft, and Perplexity Are Promoting Scientific Racism in Search Results (Wired)