Bypassing Surveillance Bans, Biometrics & the 5th Am., NY FOIL Reform Bill, Police ALPR Sharing & More

Vol. 6, Issue 7

July 7, 2025

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. This month, Diane Akerman discusses how police thwart surveillance restrictions by sharing data and resources. Gregory Herrera analyzes a recent New York appellate court decision on the Fifth Amendment’s applicability to compelling a person to use their fingerprint to unlock a phone. Laura Moraff reviews the passing by the New York State Assembly and Senate of a bill to update the Freedom of Information Law. Finally, guest columnist Martin Berg examines how local police share automated license plate reader data with federal law enforcement.

The Digital Forensics Unit of The Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal Defense, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of The Legal Aid Society.

In the News

Who Will Police the Police: Law Enforcement Regularly Circumvents Prohibitions on Surveillance Technology

Diane Akerman, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

One of the greatest threats to our privacy is not just the digital footprint we leave behind, but the ways in which those footprints are aggregated and then shared. While initially this information was collected for profiteering purposes, it has become more and more common for law enforcement to obtain and use this data. Not only to circumvent 4th Amendment warrant requirements, but local prohibitions.

Information obtained via public records requests show that a group of analysts working across southern Oregon created a listserv where officers in one jurisdiction could ask for assistance - through non-traditional channels - for obtaining data they otherwise wouldn’t have access to. The information sharing potential violated sanctuary city laws, bans on certain surveillance technology, and bans on aiding investigations into abortions and other crimes. Most importantly, it’s a major violation of public trust. Kelly Simon from the American Civil Liberties Union of Oregon told 404 Media:

“Oregon has really strong firewalls between local resources, and federal resources or other state resources when it comes to things like reproductive justice or immigrant justice. We have really strong shield laws, we have really strong sanctuary laws, and when I see exchanges like this, I’m very concerned that our firewalls are more like sieves because of this kind of behind-the-scenes, lax approach to protecting the data and privacy of Oregonians.”

In another case, local police in Mount Prospect, Illinois are under investigation for providing license plate reader information (via their use of Flock) to Texas law enforcement investigating a potential criminal case against a woman who obtained an abortion. The report revealed that Mount Prospect also shared automated license plate reader (ALPR) information in over 200 immigration related cases. As a result of these revelations, the department has opted out of Flock's nationwide lookup. Read this issue’s Expert Opinions column for more information on ALPR data being shared with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

A data broker called Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC) has also been sharing their information with Customs and Border Patrol, giving them access to not only passenger manifests, but billing and personal information far beyond that they otherwise have access to. CBP claimed access was necessary “to support federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to identify persons of interest’s US domestic air travel ticketing information.”

ARC - or rather the domestic airlines collecting the data - were well aware of the unpopularity of sharing data with ICE, and included in their contract a clause asking CBP to “not publicly identify vendor, or its employees, individually or collectively, as the source of the Reports unless the Customer is compelled to do so by a valid court order or subpoena and gives ARC immediate notice of same.” (The irony of asking CBP to comply with legal process - while providing them access to data precisely in order to circumvent legal process, warrants a chuckle.)

This clause, and the swift policy changes in other cases, highlights one positive. While it often doesn’t seem like it, it remains, in many ways, publicly unpopular to cooperate with immigration enforcement.

In the Courts

iPlead the Fifth: Fourth Dept. Says No to Compelling Biometric Data to Unlock Phones

Gregory Herrera, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

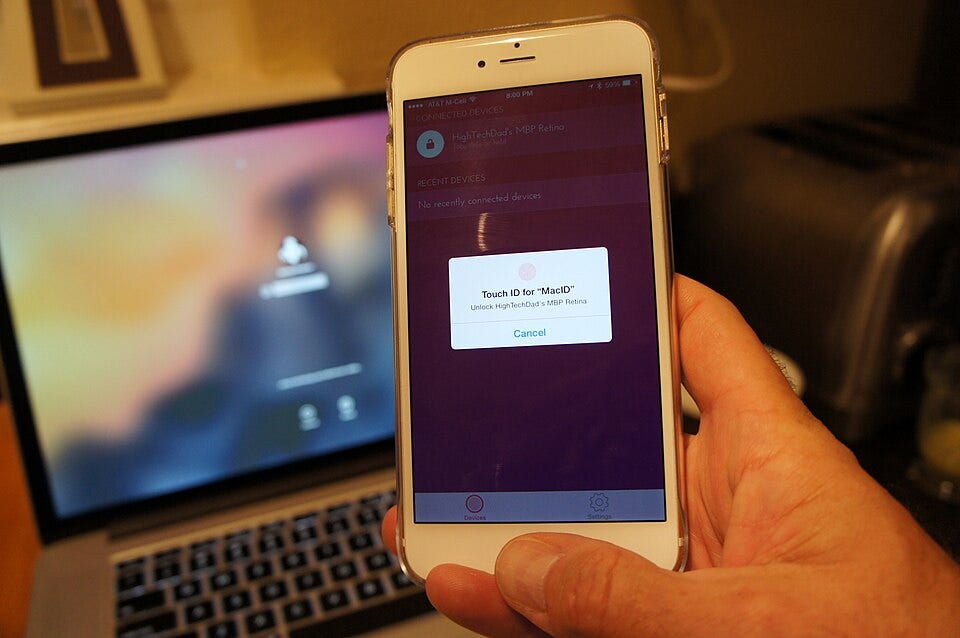

On June 27, 2025, the Fourth Department unanimously decided in People v. Manganiello that compelling a defendant to provide their biometric data to unlock a cell phone – when its ownership is in dispute – violates the Fifth Amendment.

The defendant was charged with possession of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) after the Oswego County Sheriff’s department received a tip from Google in 2022 that the material was uploaded to its servers from a specific Google account. The information Google provided eventually led investigators to an address from which the account was accessed, and they applied for a warrant to search the defendant and electronic devices in his possession. Crucially, the warrant application stated that “it will likely be necessary to press the finger(s) of the user of the device(s) found during the search to the biometric sensor, or make the user(s)’ face visible to the scanner, in attempt to unlock the device for the purpose of executing the search.” The County Court gave its blessing and said that officers “may, if necessary,” force the defendant to unlock any devices with his fingerprint or face.

When executing the warrant, the defendant was ordered to hand over his cell phone. When the investigator tried to grab it, the defendant “pulled away” but was detained and arrested. After being told that the warrant required him to unlock the cell phone, the defendant did so by using his fingerprint. The trial court rejected the defendant’s challenges under the Fourth and Fifth Amendments. Eventually, he pled guilty.

In its decision, the Fourth Department began by stating the rule for invoking Fifth Amendment privilege: the relevant communication must be 1) compelled; 2) incriminating; and 3) testimonial. It explained that testimonial communications explicitly or implicitly relate a factual assertion or disclose information, and that delineating those is a contextual inquiry.

Well, is the act of opening a cell phone with biometric data a “testimonial communication”? The Court laid out the two divergent roads in the legal woods: 1) “physical trait” cases where certain acts like standing in a lineup or a handwriting sample are not testimonial and 2) “act of production” cases where physical acts can be testimonial if the act communities the existence of control or authenticity of evidence.

Comparing and contrasting two recent Court of Appeals decisions helped the Fourth Department reach its conclusion. It examined U.S. v. Payne, 99 F.4th 495 (9th Cir. 2024) [PDF], in which the Ninth Circuit held that police officer’s forcible use of the defendant’s thumb to unlock a phone did not violate the Fifth Amendment because it was not a testimonial act. The Fourth Department wrote that “Payne had already acknowledged ownership of the phone and where it was located by telling a police officer that it ‘was in the driver’s door panel and was green in color’” and that the Ninth Circuit’s decision turned on “Payne’s concessions.” It’s worth digging a bit deeper into Payne because that’s not quite the case.

The Ninth Circuit found that the forced unlocking did not require “cognitive exertion.” In other words, the officer placing the defendant’s thumb on the phone did not reveal the contents of the defendant’s mind and was, therefore, not a testimonial act. Because these analyses are fact-specific, it’s important to note two things. First, the defendant in Payne was on parole at the time of his arrest and under special conditions to surrender any electronic device and passkey/code to law enforcement under threat of confiscation of the device or arrest pending investigation. Second, the defendant didn’t just tell the police where the phone was located and its color, he quickly denied ownership of the phone and knowing its password after being told to unlock it. The Ninth Circuit could have relied on those facts to find that ownership in dispute (as the Fourth Department said it did) and still reached the same conclusion with a tidier analysis. Nonetheless, the Ninth Circuit went on say that their “opinion should not be read to extend to all instances where a biometric is used to unlock an electronic device.”

The Fourth Department also examined the District of Columbia (D.C.) Circuit’s ruling in U.S. v. Brown, 125 F.4th 1186 (D.C. Cir. 2025) [PDF], where a defendant’s compulsory opening of a cell phone with his thumbprint was indeed a testimonial communication in violation of the Fifth Amendment. The forced unlocking disclosed the defendant’s ownership or control over the phone and its content as well as his knowledge of how the phone opened. It’s worth digging deeper here too. The FBI agent in Brown testified he found a cell phone in the defendant’s home after executing a search warrant and after the defendant was in custody. The agent asked the defendant for the password to the phone, and the defendant offered three options. None of them unlocked the device. Then the agent returned and was “able to obtain [the defendant’s] thumbprint to open the phone,” though he couldn’t remember exactly “how that was done” or his conversation with the defendant. He testified that it was his “ordinary practice” to ask defendants if they wanted to access the phone to retrieve phone numbers that they can later call in jail. The government initially argued that the defendant had consensually given his thumbprint to unlock the phone but then conceded that the defendant had been compelled to give up his fingerprint. The D.C. Circuit found that “his act of unlocking the phone represented the thoughts ‘I know how to open the phone,’ ‘I have control over and access to this phone,’ and ‘the print of this specific finger is the password to this phone.’” Additionally, unlike a blood draw that only reveals blood-alcohol level content after a chemical analysis, the compelled opening of a phone via biometric data needs no additional information to understand that it directly reveals an individual’s ownership of the phone and knowledge of how to open it.

Turning back to Manganiello, the Fourth Department agreed with the D.C. Circuit and ruled that the way the warrant was executed “effectively required the defendant to answer ‘a series of questions about ownership and control over the phone, including how it could be opened and by whom.’” Compelling the defendant to unlock the phone was testimonial and therefore a violation of the Fifth Amendment. The fact-specific ruling was careful to state that it did not consider whether a search warrant could allow officers to press a defendant’s fingers on a phone under the Fifth Amendment, or whether the New York State Constitution would grant greater protection than the Federal Constitution if it considered facts similar to Payne. Even so, it’s great news for the Constitution that the Fourth Department gave the Fifth Amendment a thumbs up.

Policy Corner

A Legislative Win for FOIL (amidst losses for most other things)

Laura Moraff, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

New York’s 2025 legislative session has come to a close, and the Digital Forensics Unit (DFU) is celebrating a major victory for transparency: the passage of S.2520/A.3425, an Act that sets maximum allowable timeframes for agencies to respond to requests for records under New York’s Freedom of Information Law (FOIL).

Access to information about government policies and practices is essential to the work we do at DFU and at The Legal Aid Society more broadly. We use FOIL to try to understand when, why, and how our clients are being monitored, what discovery should be available in a criminal case, and where to focus our advocacy in order to make New York a better and freer place. But, in practice, our efforts to get this information are often delayed for weeks, months, or even years, without justification. While FOIL requires that agencies acknowledge records requests within five business days, its text does not prohibit agencies from continuously extending their time to respond. Excessive delays have become the norm, and the system desperately needs reform.

The new legislation reforms the process by capping the amount of time an agency can take to produce responsive records. For FOIL requests submitted before December 31, 2026, the Act requires agencies to produce responsive records within 180 days. For FOIL requests submitted in 2027, agencies must produce responsive records within 90 days. And starting in 2028, agencies will be required to produce responsive records within 60 days. Unfortunately, as the legislative session was coming to a close, there was an exception added to the Act for when “responsive records are so voluminous that the agency could not reasonably review such records within the relevant timeline.” While we are concerned that this provision may be abused, we are hopeful that the Act will be implemented as intended and will significantly cut down on wait times across the board.

It is especially notable that this bill passed given how truncated this legislative session was. The New York State budget was finished more than a month late, which restricted the time available to pass much needed legislation. Other bills DFU was supporting—including a ban on reverse location and reverse keyword searches, and restrictions on biometric surveillance in schools, public accommodations, residences, and law enforcement—failed to pass. But the legislature understood the urgency of fixing our broken FOIL system; we call on the Governor to do the same and sign S.2520/A.3425 into law.

Expert Opinions

We’ve invited specialists in digital forensics, surveillance, and technology to share their thoughts on current trends and legal issues. Our guest columnist this month is Martin Berg.

A Song of ICE and Fire: How Local Police Departments Help the Feds Surveil Us

On March 7, 2025, Colorado officers with the Loveland Police Department monitored a smoldering grease stain at the local Tesla dealership. The odor of gasoline was conspicuous in the parking lot full of electric cars. This would be the fifth incident of (attempted) arson at the Tesla dealership since the end of January. The Loveland Police Department announced the same day that they would be requesting the help of federal agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF).

Twenty days later, Cooper Frederick of Fort Collins, Colorado, was arrested in Frisco, Texas and soon indicted by a federal grand jury. On April 1, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Colorado announced that the prosecution “is being handled by the Violent Crimes and Immigration Enforcement Section of the United States Attorney’s Office.”

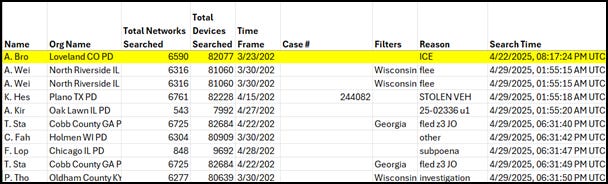

The Loveland Police Department in late June admitted that it gave the ATF access to its Flock account within the last few months. Flock Safety is a company that sells license plate reader (LPR) cameras typically installed in parking lots, on highways, or at intersections. These cameras are an immensely powerful surveillance tool, capturing not only the license plate, but the make, model, and color of the vehicle observed. Officers can then sift through the data captured by every camera connected to the Flock network. Data published by MuckRock show that in March and April, an account associated with Loveland Police searched the national Flock database on multiple occasions listing “ICE” as the reason for the search. Loveland Police point the finger at an unnamed ATF agent using their account.

Despite Flock Safety not directly contracting with ICE, local law enforcement agencies have been sharing their LPR data with the agency for the purpose of immigration-related investigations. This “side-door” access has been used across the country, with law enforcement agencies at times citing “HSI” (Homeland Security Investigations) or “ICE” as their reason for requesting the data. It is impossible to know from the data precisely how many searches are immigration-related, as reasons such as “case,” “FLOCK,” and “investigation” are also inputted.

Agencies that directly contract with Flock can opt in to share their LPR data with the national network. Those with access to Flock can then search LPR data nationally, identifying a target vehicle in one state and tracking it to another. One search made by the Loveland Police Department account under the name “A. Bro” rummaged through 6,590 Flock camera networks listing “ICE” as the reason. In total, 82,077 cameras were accessed in a single search by a federal agent for immigration enforcement.

In the case of Loveland County, an arson investigation wedged a federal foot in the door of LPD’s Flock account (despite Colorado law prohibiting cooperation between police and immigration authorities). Federal mass surveillance has, in this instance, been privatized by a third party who uses local police departments as individual nodes in a national dragnet. Access, legal or illegal, to that vast trove of surveillance data is as secure as any one police department’s username and password. More than 600 state and local agencies have officially partnered with ICE.

Flock has allegedly removed the "national lookup feature" for cameras in some states, likely to force compliance with state law. The Illinois Secretary of State is investigating whether Illinois police departments broke a state law preventing data sharing with outside agencies. Beyond illegally sharing data for immigration enforcement purposes, the police department of Mount Prospect, Illinois, illegally provided LPR data with a Texas sheriff hunting for a woman seeking healthcare in Illinois. Accordingly, Flock says they have limited out-of-state agencies' ability to search LPR cameras in Illinois, California, and Virginia.

Martin Berg joined the New York State Defenders Association in September 2024 as a Discovery & Digital Evidence Law Graduate after graduating from Emory University School of Law. Before attending law school, Martin earned a B.A. in Mechanical Engineering and Religious Studies at Rice University. Working with public defenders since 2019, Martin specializes in processing digital forensic evidence, particularly cell site location information. Martin previously served as a legal intern with the Georgia Capital Defender Office, the Dekalb Public Defender Office, and the Georgia Public Defender Council in Fulton. In 2024, he took home a national championship victory at the John L. Costello Criminal Law Mock Trial Competition. In his spare time, Martin enjoys woodturning, embroidery, and travelling throughout New York State.

Upcoming Events

July 8-9, 2025

Harnessing AI for Forensics Symposium (RTI International & NIST) (Washington, DC)

July 9, 2025

Artificial Intelligence, Real Consequences: Ethical Duties in a Synthetic Era (NYS Trial Academy) (Virtual)

July 11-12, 2025

Summercon (Brooklyn, NY)

July 17, 2025

Artificial Intelligence in Law Practice 2025 (PLI) (New York, NY and Virtual)

July 26, 2025

Privacy Self-Defense & Immigration Know Your Rights (Secure Justice) (San Francisco, CA)

August 4, 2025

The Diana Initiative 2025 (Las Vegas, NV)

August 4-6, 2025

BSides Las Vegas (Las Vegas, NV)

August 7-10, 2025

DEF CON 33 (Las Vegas, NV)

August 15-17, 2025

HOPE 16 (Queens, NY and Virtual)

September 9-11, 2025

Amped User Days (Amped Software) (Virtual)

UC Berkeley Law AI Institute (Berkeley, CA and Virtual)

October 13-14, 2025

Artificial Intelligence and Robotics National Institute (ABA) (Santa Clara, CA)

October 21-23, 2025

Legacy & Logic: 25 Years of Digital Discovery (Oxygen Forensics) (Orlando, FL)

October 27-29, 2025

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference West (San Diego, CA)

October 27-31, 2025

36th Annual LEVA Training Symposium (Coeur d’Alene, ID)

Small Bytes

An LAPD Helicopter Claimed Cops Identified Protesters From Above and Would “Come to Your House” (Mother Jones)

Android 16 introduces Advanced Protection mode to fortify your phone against threats (Android Authority)

Who Owns the Future? Ways to Understand Power, Technology, and the Moral Commons (Tech Policy Press)

They Asked an A.I. Chatbot Questions. The Answers Sent Them Spiraling. (NY Times)

We caught 4 more states sharing personal health data with Big Tech (The Markup)

State Department unveils social media screening rules for all student visa applicants (Politico)

How My Reporting on the Columbia Protests Led to My Deportation (The New Yorker)

‘FuckLAPD.com’ Lets Anyone Use Facial Recognition to Instantly Identify Cops (404 Media)

I Tried, and Failed, to Disappear From the Internet (NY Times)

ICE Is Using a New Facial Recognition App to Identify People, Leaked Emails Show (404 Media)

The Trump administration is building a national citizenship data system (NPR)

ICEBlock: This iPhone app alerts users to nearby ICE sightings (CNN)