Digital Forensics on Trial, Data Privacy, ShotSpotter Discovery Decision, Cellebrite Extractions & More

Vol. 4, Issue 3

March 6, 2023

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. In this issue, Lisa Brown discusses digital forensics evidence in the Murdaugh homicide trial. Brandon Reim reveals how companies acquire and use your personal data. Jerome Greco reviews a recent decision concerning the ShotSpotter gunshot detection system and discovery. Finally, Chris Pelletier explains how to open and review a Cellebrite extraction report.

The Digital Forensics Unit of the Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts and examiners, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of the Legal Aid Society.

In the News

Digital Forensics on Trial: Analyzing Passcode Cracking and Evidence Handling in the Murdaugh Case

Lisa Brown, Digital Forensic Analyst

Former South Carolina lawyer Alex Murdaugh was found guilty last week for the murder of his wife, Maggie Murdaugh, and their son, Paul Murdaugh. Two notable digital forensics issues emerged at trial. First, a Secret Service agent gained access to a decedent's locked iPhone to retrieve key evidence. Second, the defense identified flaws in law enforcement’s method of preserving digital evidence.

Issue #1: Accessing Paul Murdaugh’s iPhone without the passcode

Prosecutors introduced a crucial video recorded by Paul Murdaugh just before he was shot and killed. A family friend testified that he could hear Alex Murdaugh’s voice in the background. This video appeared to contradict Murdaugh’s original alibi that he was napping at that time of the shooting.

How was South Carolina law enforcement able to get this video from a decedent's locked iPhone without the passcode? They did not get any help from Silicon Valley. Apple is unable and unwilling to assist law enforcement with accessing data on locked devices. However, mobile forensics companies like Cellebrite and Grayshift have created tools that attempt to unlock phones by trying every possible passcode combination - a form of “password-cracking” - without locking or resetting them.

At trial, a police officer testified that he had access to the password-cracking tool GrayKey (made by Grayshift), but was unable to determine the passcode for this particular iPhone model and iOS version. Whenever Apple releases an update to their software, researchers must develop new ways around the corresponding security updates. This is why newer iOS versions are not always supported by these cracking tools. The officer contacted the Secret Service because they have access to another password-cracking tool, Cellebrite Premium, which supported the iPhone version in question.

Even with access to GrayKey and Cellebrite Premium, cracking an iPhone’s passcode is not guaranteed. The Secret Service agent testified that Cellebrite Premium is limited to attempting one passcode every 15 minutes. With this limitation, guessing a 4-digit numeric PIN could take up to 68 days, while a six-digit numeric PIN could take up to 19 years. The agent testified that because most people use a significant date as their passcode, he creates a unique list of socially engineered codes to use before the system begins trying every possible numerical combination. A passcode associated with Paul’s birthday worked to unlock the phone. One can only imagine the touchdown dance this agent must have performed when one of his guesses unlocked the phone. If this phone was locked with a truly random 6-digit pin or an alphanumeric passcode, it’s unlikely that this video would have been uncovered with the tools that are currently available.

Issue #2: Properly securing devices offline

When mobile devices are collected as evidence, it is considered best practice to block incoming and outgoing phone signals to prevent the destruction of data on the device. If a device remains online, new incoming phone calls could overwrite older call logs, or a device owner could remotely wipe the phone from another device through iCloud. Turning on airplane mode or putting the phone in a signal-blocking Faraday bag are common methods for securing a phone offline. Enabling airplane mode prevents changes to a device by turning off all of the phone’s radio transmissions. A properly sealed Faraday bag provides electromagnetic shielding to the device inside of it.

During the Murdaugh trial, the prosecutor’s analyst testified that their process to secure mobile device evidence offline is to enable airplane mode on the phone and remove its SIM card. They do not use any physical shielding, such as Faraday bags. While placing a phone in airplane mode is generally considered sufficient for the purposes of preventing remote wiping, it does not block the phone’s GPS function, and the phone can continue to collect new location data. This was apparent in a police department photo (displayed above). The photo showed that even though the phone was in airplane mode, the phone’s location services were still actively functioning, as indicated by the black arrow in the top left corner of the phone screen.

The prosecutor’s analyst testified that when they checked Maggie Murdaugh’s phone extraction for location data, the oldest entry was from June 9. There was no location information from the incident date of June 7. The analyst explained that the location databases can only hold a limited amount of data before they get overwritten with new location data.

The defense put an expert on the stand who testified that if Maggie Murdaugh’s phone had been secured in a Faraday bag, the GPS signal would have been blocked, new location data would not have been logged, and location data from the date of the incident would have been preserved. This testimony illustrates the distinction between airplane mode and physical shielding, which is often overlooked by those tasked with preserving mobile device evidence.

It will be interesting to see how topics like the ones discussed here, breaking into locked phones and safeguarding digital data, present in future cases. These issues will only become more prevalent as digital evidence is now regularly introduced in court.

Data Privacy in our Everyday World

Brandon Reim, Digital Forensic Analyst

When Disneyland opened in 1955, people lined up with paper tickets eagerly awaiting what “The Most Magical Place On Earth” had to offer. There were stories of counterfeit tickets, people with ladders scrambling over the barbed wire fence, or even walking into the park without a ticket. Today, everything is done electronically. Most often, tickets at Disney are used with an app or a “magic band” (RFID band). These “magic bands” have your information, credit card, and ticket, making it easy to go wallet free. Although some might not be concerned at the amount of information companies are collecting, it is something we should all consider.

Recently, Janet Vertesi explained her attempts to prevent Disney from knowing anything about her family. Using fake names, a VPN (Virtual Private Network), and refusing to utilize Disney’s “convenience” system, she did everything she thought possible to protect her family’s identity in the name of data privacy. For instance, Disney uses its “My Disney Experience” app to enter parks, order food, join virtual lines, and more. In Orlando, the Disney app and the “magic bands” make the experience simple. Just a tap of the band or your phone on a cute Mickey logo, and you can buy food with your linked credit card, join a Lightning Lane, or access your on-site hotel room. All those data points are being tracked. These data points, along with your personal data, can easily be used by Disney to sell products and design personalized marketing campaigns. Considering this, why do people so willingly give their information to Disney? For most, it’s convenience. Paper tickets are easy to lose and carrying your wallet around is a hassle on rides. For others, data collection never crosses their mind. Additionally, as Vertesi demonstrated, it is difficult to opt-out.

Most people who attend a sporting event or show do not consider the data they are voluntarily handing over. For example, the controversy surrounding the use of facial recognition at Madison Square Garden took many by surprise. People did not expect their faces would be scanned, processed, and used to determine whether they would be allowed into an arena. Another example is the Super Bowl, which only used electronic tickets this year. Even the World Cup was affected, requesting its attendees to give access to their entire phone when installing and using their app.

Disney is just one of the entities that will track everything you do at its venues and use it to “better serve” you. Data privacy is something we take for granted in our everyday lives. Creating false identities, using burner phones, and refusing all convenience may not be worth the trouble for most people at Disneyland, but we should all be more thoughtful when providing a corporation with our name, email, birthday, address, and payment information.

In the Courts

ShotSpotter Materials are Within the NYPD’s Custody and Control, and are Automatically Discoverable

Jerome D. Greco, Digital Forensics Supervising Attorney

In People v. Gutierrez (2023 NY Slip Op 23022 [Bronx Co. Sup. Ct. 2023]), a Bronx County Supreme Court Justice granted a motion to dismiss, finding that the prosecution’s statement of readiness and certificate of compliance were illusory partly “[b]ecause the People failed to demonstrate that they have exercised due diligence and good faith to procure the relevant ShotSpotter information.” Id. at *5-*6. I do not endorse all the court’s findings, particularly as it relates to the prosecution’s original alleged exercise of due diligence and good faith, but the ultimate determinations regarding the discoverability of ShotSpotter evidence will be useful in future cases.

Regarding the prosecution’s refusal to provide the ShotSpotter related discovery, the ADA argued that “ShotSpotter belongs to a private company” and that the records were not in the DA or NYPD’s “custody and control.” Id. at *3. The Court rejected these claims and found that ShotSpotter records were within the NYPD’s custody and control. The Court also “conclud[ed] that ShotSpotter records constitute items that must be provided to defense counsel as part of automatic discovery under CPL Article 245.20(1)(e) or (g).” Id. at *4.

Importantly, the Court cited both to the ShotSpotter Impact and Use Policy [PDF], which the NYPD was required to release under the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology (POST) Act, and to a recent Bloomberg article featuring the work of Digital Forensics Unit member, Benjamin Burger. Addressing the prosecution’s arguments, the Court determined

“While it is true that ShotSpotter is an independent entity, as the People assert, the Policy Statement makes it abundantly clear that the NYPD has access to a substantial amount of data, if not all of the data, generated and maintained by the company. In fact, the Policy Statement provides, ‘[i]f ShotSpotter data is relevant to a criminal case, the NYPD will turn the data over to the prosecutor with jurisdiction over the matter,’ not the company’s discovery compliance unit.”

Gutierrez at *5.

The POST Act was viewed by most advocates as a small step in a larger fight against the problem of NYPD surveillance, not a solution. Its most significant value is the ability of defense attorneys to learn about these tools through the Impact and Use Policies, and to use those policies as weapons in our individual client cases.

Legal Aid Society attorney Kyla Wells’ “persistent[] and steadfast[]” demands for the ShotSpotter materials and her inclusion of the Impact and Use Policy in her motion, among other steps, resulted in the dismissal of her client’s case.

Furthermore, the Gutierrez decision potentially has broader implications. Prosecutors across New York City have consistently argued that body-worn camera audit trails are not discoverable. One of their arguments is that the audit trails are not in the “custody and control” of the NYPD or the prosecution because they are stored in Evidence.com, which is controlled by Axon, a “private company.” Like ShotSpotter materials, the NYPD has full access to the audit trails. From experience, we know they are provided whenever the prosecution requests them, or a court orders their release. Law enforcement cannot avoid their discovery obligations by storing the materials with a private company.

Ask an Analyst

Do you have a question about digital forensics or electronic surveillance? Please send it to AskDFU@legal-aid.org and we may feature it in an upcoming issue of our newsletter. No identifying information will be used without your permission.

Q. I have a cell phone extraction report from Cellebrite, how do I look at it?

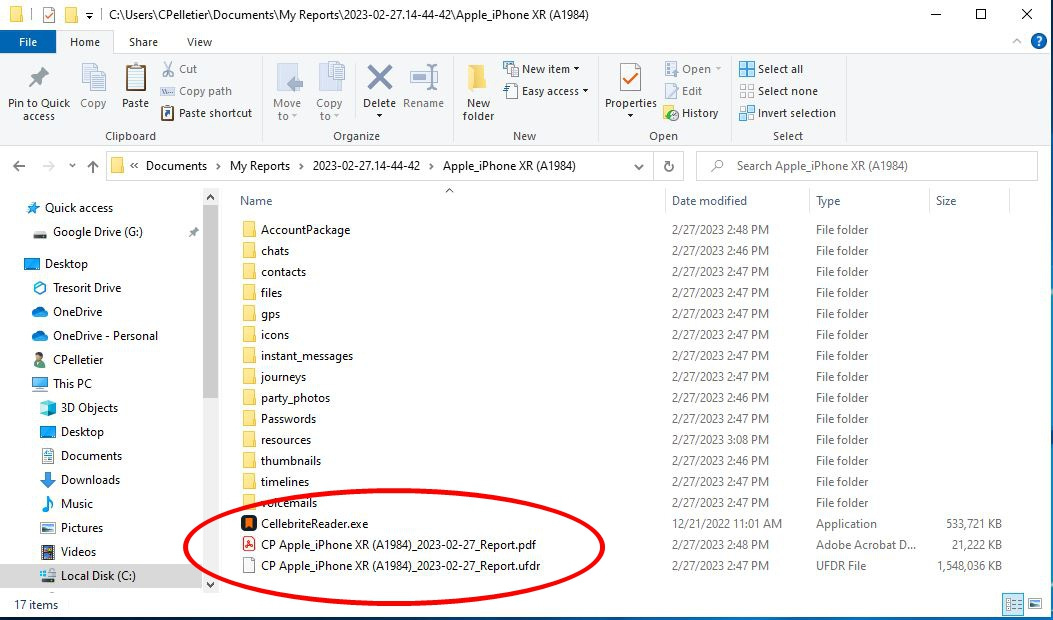

A. You received a Cellebrite mobile phone extraction report, maybe as discovery from the DA, maybe from your own expert witness like a member of the Digital Forensics Unit. When you look at it on your computer, you will see many nested folders and files. You may not be sure where to begin. There's no need to panic. It's not as hard as you might think! Usually when you're given an extraction report, it's given to you either as a PDF file that you can open and scroll through using a PDF reader like Adobe, or as a UFDR file in conjunction with a program called Cellebrite Reader. Cellebrite Reader opens on your computer (Windows required!) and allows you to navigate through the information. They may look something like this:

If the folders look similar to the above picture, you can start by reviewing the PDF report. Look for the file ending in .pdf and double click on it with your left mouse button. It should open up the PDF reader on your computer. The report should look like this:

You can now use the arrows on the top navigation bar to page up and down through the report. You can also use the Bookmarks column on the left to see the headings for the different types of information contained in the report. By left clicking on the Bookmark heading name (such as “Device Information”, circled in the image above) it will take you directly to that category and it will show that information in the middle of the page. You can also simply left click and hold on the scroll bar on the right of the page and drag it up and down and it will scroll you through the report.

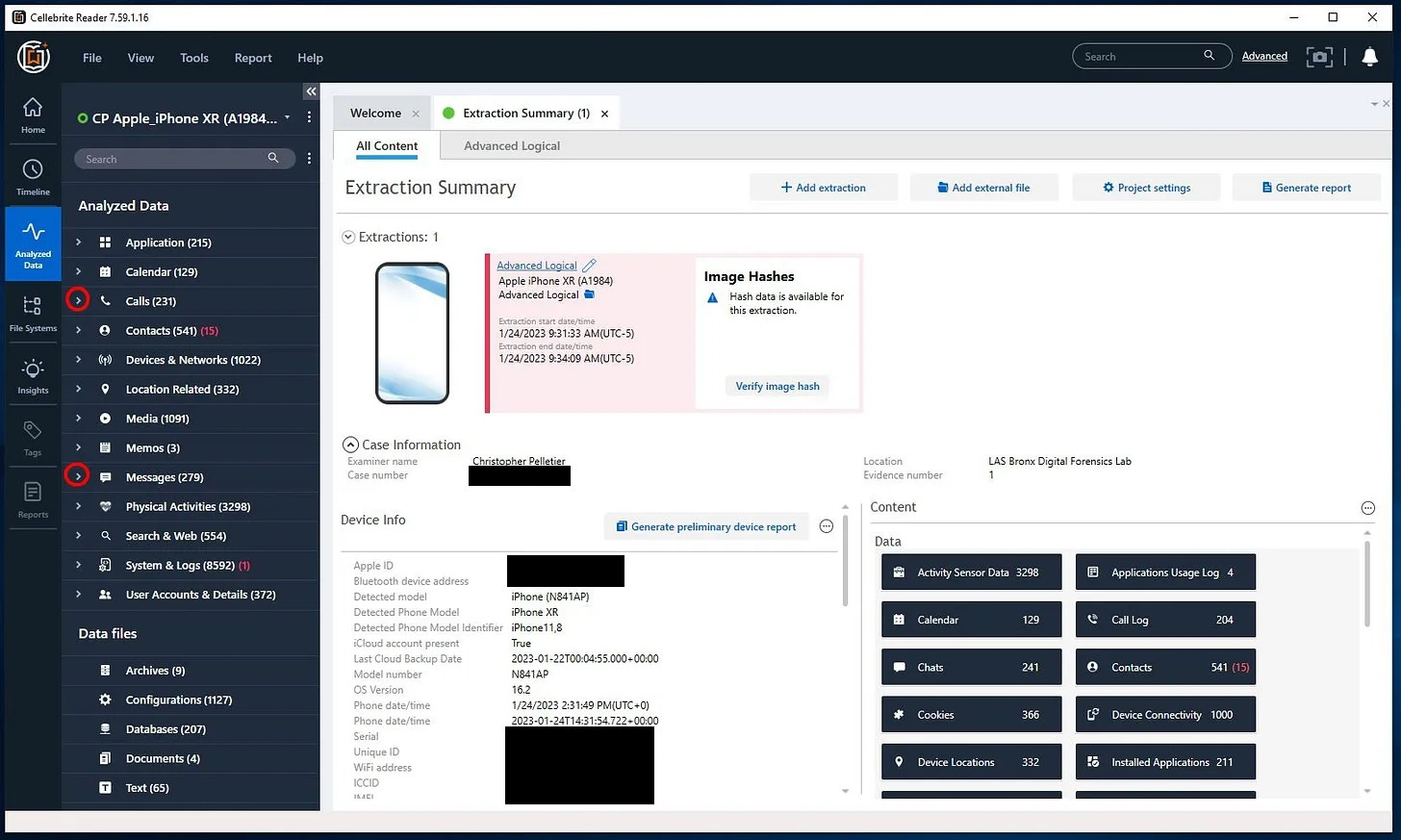

The second way to view the extraction report is to use the provided Cellebrite Reader program. This is the preferred way to receive, view, and analyze an extraction report. When you navigate to the folder on your computer, look for the file named “CellebriteReader.exe” and double click on it with your left mouse button. Give it a few minutes to load (it may take a while depending on your computer) and it will open up the Cellebrite Reader program. A “Cellebrite Reader Activation” window will pop up and you can just left click on “Activate Later”. You also may have a “Device time zone detected” window pop up. You can left click on "Yes" to use the device’s local time. You should now have the Reader program open on your computer (see below):

On the left you'll see a vertical navigation bar with the word “Home” at the top. If you look down from “Home” and left click on “Analyzed Data”, it will expand the headings for the different types of information contained in the report, similar to the Bookmarks shown in the PDF version.

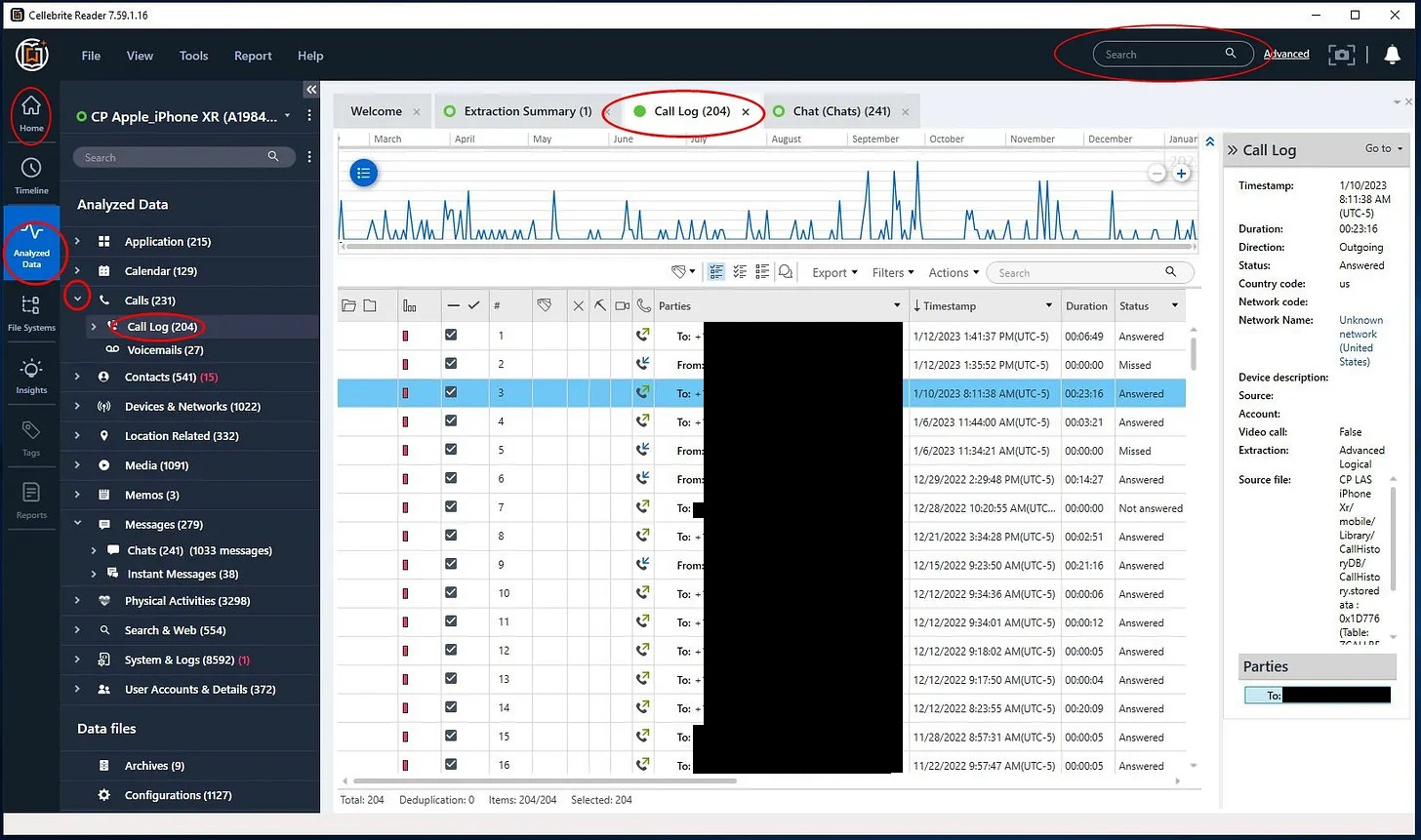

You can now left click on the “>” to the left of any of these heading names (such as "Calls" or "Messages") and you'll see subcategories such as "Call Log" or "Chats". Double click with your left mouse button on one of these subcategory names to open a tab in the middle of the page containing that information. You can then scroll through that information and sort on any of the columns contained therein.

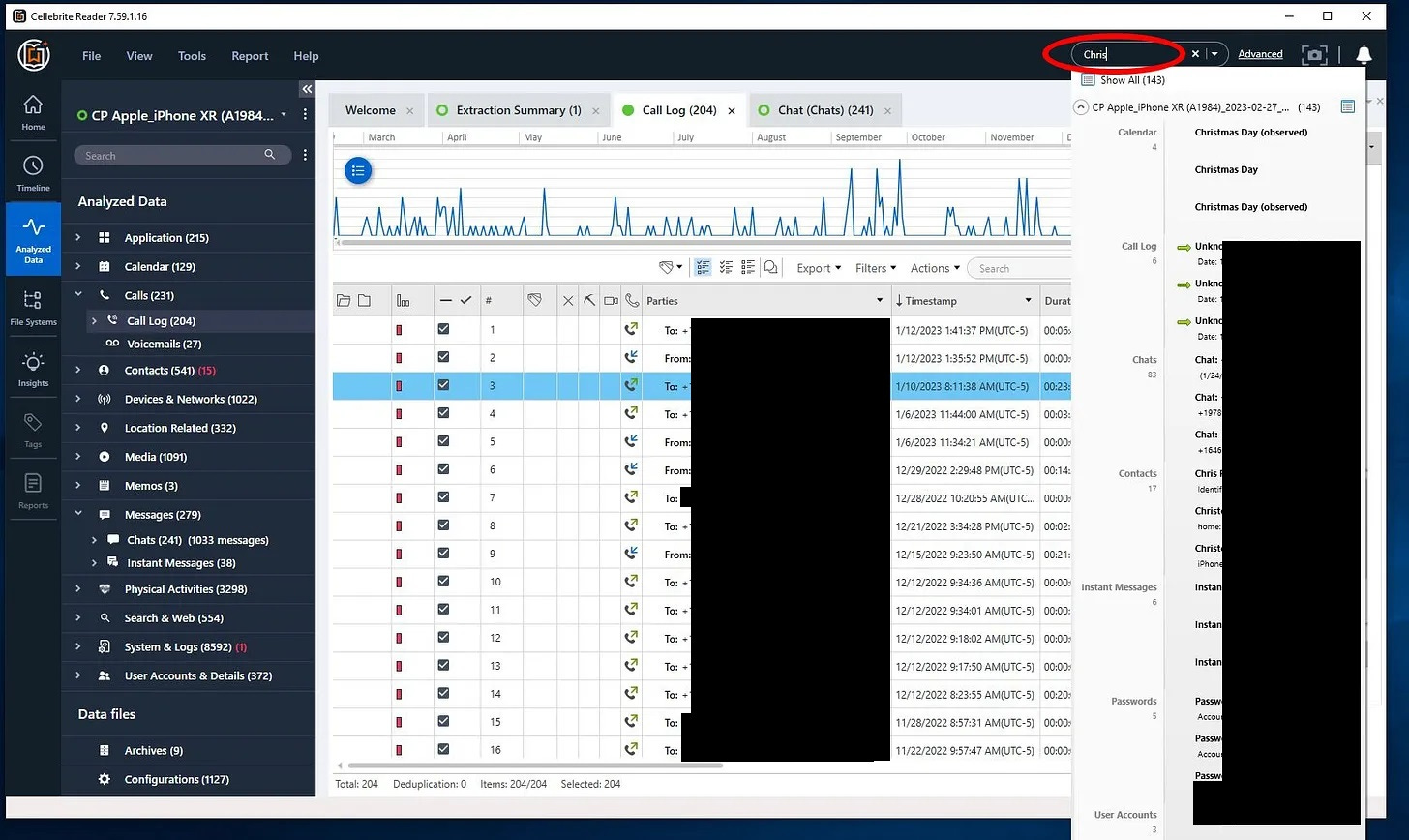

At the very top right of the screen you'll see a Search window where you can type in any search term and if found it will present a drop down list of the search hits. Clicking on any of these search hits will then open another tab with that particular information.

These are just some of the ways you can browse through your extraction data. Keep in mind that an extraction report may not contain all the information from the complete phone extraction.

Chris Pelletier, Digital Forensic Analyst

Upcoming Events

March 11-18, 2023

Open Data Week 2023 (Various Locations in NYC)

March 20, 2023

Meredith Broussard: Bias Is More than a Glitch (NYPL) (New York, NY & Virtual)

March 20-24, 2023

MozFest (Mozilla) (Virtual)

March 23, 2023

Who Watches the Watchers?: Surveillance and the Law (Brooklyn Law School) (Brooklyn, NY)

April 17-19, 2023

Magnet User Summit (Magnet Forensics) (Nashville, TN)

April 22, 2023

BSidesNYC (New York, NY)

April 27, 2023

Decrypting a Defense (Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit) (CUNY Law School, Queens, NY) (external registration coming soon!)

April 27-29, 2023

16th Annual Forensic Science & The Law Seminar (NACDL) (Las Vegas, NV)

June 5-8, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference East (Wilmington, NC)

August 10-13, 2023

DEF CON 31 (Las Vegas, Nevada)

September 11-13, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference West (Pasadena, CA)

Small Bytes

How US police use digital data to prosecute abortions (TechCrunch)

Data privacy after the fall of Roe (Politico)

‘Without Fear of Retribution’: NY State Bar Forms Group to Study Facial-Recognition Blacklisting of Lawyers From MSG, Radio City (New York Law Journal)

Developers Created AI to Generate Police Sketches. Experts Are Horrified (Vice)

Facing Bias: CBP’s Immigration App Doesn’t Recognize Black Faces, Barring Thousands from Seeking Asylum (The Border Chronicle)

The FBI’s Most Controversial Surveillance Tool Is Under Threat (Wired)

How Citizen is trying to remake itself by recruiting elderly Asians (MIT Technology Review)

AI Use by Cops, Child Services In NYC Is a Mess: Report (Vice)

US Military Signs Contract to Put Facial Recognition on Drones (Vice)