Federal Watchlists for Protesters, Ghost Gun Bogeyman, ALPR Virginia Court Decision, File Signatures and Carving & More

Vol. 7, Issue 2

February 2, 2026

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of The Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. This month, Gregory Herrera discusses secret federal watchlists used to track protesters. Next, Shane Ferro criticizes a new attempt in New York to ban ghost guns and digital blueprints and restrict the capabilities of 3D printers. Then, Diane Akerman analyzes a decision on automated license plate readers from the Eastern District of Virginia. Last, Chris Pelletier explains file signatures and file carving.

In the News

Watching Every Move You Make

Gregory Herrera, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they haven’t been watching you. On Jan. 28, 2026, independent journalist Ken Klippenstein reported on the various secret watchlists that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has compiled to track protestors. These watchlists go by codenames such as “Bluekey, Grapevine, Hummingbird, Reaper, Sandcastle, Sienna, Slipstream, and Sparta,” according to Klippenstein’s conversation with senior national security officials.

There’s almost no information available to indicate the purpose or scope of these watchlists. Though at least one of them was designed to vet and track immigrants, others are designed to map relationships and link people together that do not have anything to do with criminality. A DHS attorney told Klippenstein that “[w]e came out of 9/11 with the notion that we would have a single ‘terrorist’ watchlist to eliminate confusion, duplication and avoid bad communications, but ever since January 6, not only have we expanded exponentially into purely domestic watchlisting, but we have also created a highly secretive and compartmented superstructure that few even understand.” Before 9/11, there were at least a dozen watchlists or databases maintained by almost as many federal agencies. Now, there are three watchlists.

These integrated watchlists are the all-too-predictable result of the synthetization of the national intelligence apparatus after 9/11. The PATRIOT Act [PDF] was passed in 2001 and greatly expanded the surveillance tools and methods of the federal government. DHS was created in 2002 [PDF], a move that combined 22 existing and separate federal departments and agencies. Funding for DHS exploded, reaching over $330 billion in fiscal year 2026. The PATRIOT Act was replaced by the USA Freedom Act [PDF] in 2015. The Washington Post recently wrote about all the tools in the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arsenal: facial recognition, license plate readers, cell phone location, digital forensics, drones. We’ve also written about the FBI spying on activists observing court proceedings and ICE purchasing tools from spyware companies. We are constantly monitored by every technology and tool available. In the years since 9/11, our leaders traded essential liberty for temporary safety in bipartisan fashion.

Now, apparently, we deserve neither. It’s important to connect the dots between surveillance and its effect on real people in real life. Even if you’ve been living under a rock, you know what’s going on throughout the United States right now — especially in Minnesota. DHS has unleashed ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) under the guise of immigration enforcement and mass deportations that President Trump promised while campaigning. People had been protesting DHS’s presence in their cities, and those protests have intensified now that federal agents have killed people with no meaningful accountability. Keith Porter Jr. was killed by an off-duty ICE agent in Los Angeles on Dec. 31, 2025. Renee Nicole Good was killed by DHS agents on Jan. 7, 2026, in Minneapolis. Alex Pretti was killed in Minneapolis by DHS agents on Jan. 27, 2026. And that’s on top of the many videos circulating online where federal agents have shoved and beaten protestors.

The plan seems to be for more and more protestors to end up on the federal watchlists Klippenstein exposed. We cannot keep letting our leaders trade our essential liberties for what they’re selling to us as safety.

The Ghost Gun Bogeyman

Shane Ferro, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

After the Supreme Court’s recent blow to New York State’s gun laws in N.Y.S. Rifle Ass’n v. Bruen, 579 U.S. 1 (2022) [PDF], Gov. Kathy Hochul and Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg have proposed a new way of criminalizing firearms in New York: a sweeping ban on 3D printed “ghost guns.” The proposed legislation in the governor’s 2026 budget would require 3D printers sold in New York to include software that would block the printing of guns or parts thereof. And in a twist that throws the First Amendment under the bus in an attempt to undermine the Second, the proposed legislation would also criminalize the possession, sale, or distribution of digital blueprints for guns.

New York is picking up where Clinton-era Democrats left off on trying to ban learning how to make a bomb on the internet. Who needs the First Amendment when there is an opportunity to fearmonger about new, dangerous technology in the service of inflating one’s “tough on crime” credentials? The reality is it’s already mostly illegal to make or possess ghost guns, and they are still a small minority of the guns out there, but those facts don’t get headlines.

Technically, the definition of ghost gun in PL 265.00(32) is any gun that is made without a serial number being stamped on it by a licensed gunsmith. When politicians talk about it, you always get the sense they are talking about 3D printing plastic guns, not blacksmiths going rogue (tangentially related). If a gun made out of plastic can shoot a projectile by way of an explosive — so if it’s useful as a gun — it is a “firearm” under the federal definition (18 U.S.C. § 921). Making and selling a firearm legally requires a license under both federal and state laws. In New York, the laws against possession of firearms still apply.

It is also not clear how big a problem 3D printed guns actually are. In a December press release, the NYPD claimed roughly 6% of the 25,000 guns seized during Mayor Eric Adams’ administration were ghost guns. Although there was a big jump between 2018 and 2022 as 3D printers became more popular, seizures of ghost guns are actually down significantly since that 2022 peak. The NYPD claims to have seized 528 ghost guns in 2022, 400ish in 2023 and 2024, and just 295 in 2025.

The problem with this legislation, in addition to the fact that it seems redundant, is that as great as getting guns off the street is in theory, in practice it only reinforces that the Second Amendment only exists for a certain kind of American. All too often, a big push by politicians for aggressive gun arrests is taken as an invitation for the police to trample over the civil liberties of Black and brown New Yorkers.

Traffic enforcement in majority-minority neighborhoods is mostly an excuse to search cars for guns. For every large stash of real guns found, public defenders see a dozen flimsy search warrants based on tips from unnamed, paid confidential informants that lead to dozens of officers destroying our clients’ houses to maybe find a single gun in a safe that there’s no indication anyone ever used. Recently, in Queens, an NYPD officer was arrested for planting evidence in order be able to make an arrest on that kind of search warrant case, then committing perjury to try to cover it up. The person who was arrested as a result had an open felony for more than a year before the DA’s office dismissed the case. The news to public defenders is not that the police acted badly to say they got a gun off the “streets,” but that anyone in power cared that the details smelled funny.

The question that arises from this proposal is not whether this will reduce the number of ghost guns in New York, but whether someone with the wrong skin color in the wrong neighborhood having a 3D printer might now be used as reason enough to grant a search warrant.

In the Courts

When Will It Be Enough (Location Data)?

Diane Akerman, Staff Attorney

The idea that your license plate is scanned is largely regarded as an acceptable trade-off for the “privilege” of driving a car. A lot of surveillance starts out this way — somewhat innocuous, mostly limited. Discussion of Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs) has taken over the news cycle recently, with the revelation that Flock’s private dragnet of cameras is being used to aid ICE, but the anti-surveillance community has been concerned about ALPRs for a long time. At what point does a little bit of acceptable surveillance cross the line into constitutional violations?

One court has weighed in. In Schmidt vs. Norfolk, the Institute for Justice represented two residents in a lawsuit against Norfolk, Virginia’s ALPR dragnet. At the time the suit was filed, Norfolk had 172 cameras on the street tracking drivers, and discovery revealed that “on days where it is known that Plaintiffs were photographed multiple times, the average distance between photographs with complete license plate matches was 3.5 and 2.5 miles, respectively, and the average duration between full plate matches was approximately 45-50 minutes.” The emphasis on known comes directly from the court decision and is doing a lot of work in that sentence. The city’s police chief even boasted, “it would be difficult to drive anywhere of any distance without running into a camera somewhere.” Yet this treasure trove of information can be accessed by anyone in law enforcement, for up to 21 days, for any reason. There’s no judicial or advance approval necessary.

This isn’t the first time an ALPR system has been challenged as violating the constitutional reasonable expectation of privacy in the whole of one’s movements. Carpenter set the stage for these kinds of challenges to location-based surveillance when it found that law enforcement needs a warrant to obtain historical cell site location information. Privacy activists believe there is little reason to differentiate this kind of wholesale gathering of location information.

The Fourth Circuit agreed with this prospect in the well-known case challenging Baltimore’s aerial surveillance program by activists from Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle. The Fourth Circuit described the city’s Aerial Investigative Research (AIR) surveillance program as creating “a detailed, encyclopedic, record of where everyone came and went within the city during daylight hours over the prior month-and-a-half . . . and was comparable to attaching an ankle monitor to every person in the city.” The court ultimately ruled that warrantless access to that data violated the Fourth Amendment.

Being photographed 2-3 times a day sounds like a pretty detailed encyclopedic record of one’s movements to me, but apparently not to the Virginia court ruling on this case. In dismissing the case the court relied on three factors: Norfolk’s ALPRs captured plates much less frequently than images of individuals in Beautiful Struggle (somewhere in the nexus between 3 times per day and 101 points per day lies your privacy), the ALPRs are clustered rather than spread evenly across the city (never mind the fact that overpoliced communities often bear the brunt of these “objective” placements and use of surveillance technology), and that because of their placement, the cameras “lose track” of individuals rather than continuously following them.

The court did briefly hint at a potential method of successfully attacking surveillance like ALPR — it may not run afoul of the Fourth Amendment alone, but what about when supplemented by other investigative techniques? This is a question that may very well be answered in the newly-filed lawsuit against the NYPD’s Domain Awareness System.

ALPR “surveillance could become too intrusive and run afoul of constitutional privacy standards at some point. But when?” Not today and not in Norfolk, Virginia, at least according to this court. But perhaps the more meaningful questions to ask are: Who makes that decision, and how can it be made when law enforcement has carte blanche to hide their use of surveillance technology from the public?

Ask an Analyst

Do you have a question about digital forensics or electronic surveillance? Please send it to AskDFU@legal-aid.org and we may feature it in an upcoming issue of our newsletter. No identifying information will be used without your permission

Q. The prosecution is claiming contraband was found on my client’s device. What did they look at and how did they find it?

A. For most of us, our mobile phones and computers are an integral part of daily life. And the information that is present on these devices is located in something called a file. A file is the basic unit of how this information is organized on a device, and is simply a group of zeros and ones, or bits and bytes, that serves a specific purpose. On any device there are files for many different purposes. There are files that contain the instructions for the processor. There are files that contain information about how the device should interface with peripherals like the keyboard or the display. Then there are files that contain data, which can be user data (such as your Word document, text message, email, or photo), or system data (such as the cookies for your web browser that keep information from your previous sessions, or call logs showing calls made and received on your phone). All the different files used for different purposes are divided into categories called file types, and these file types can be identified in a couple different ways.

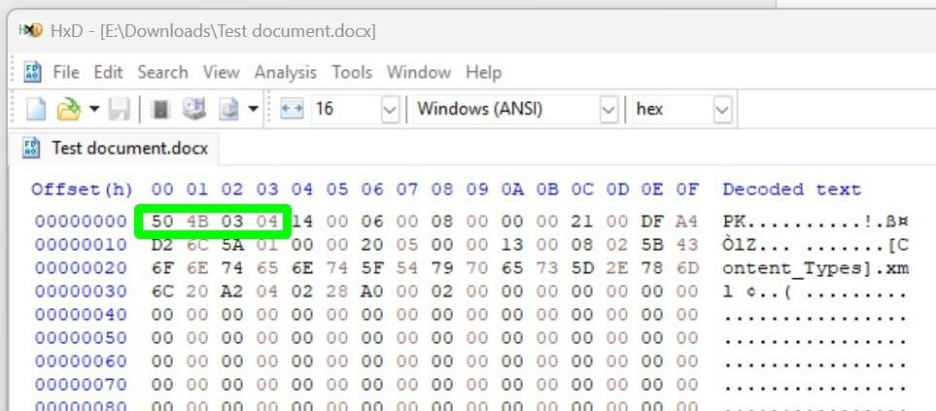

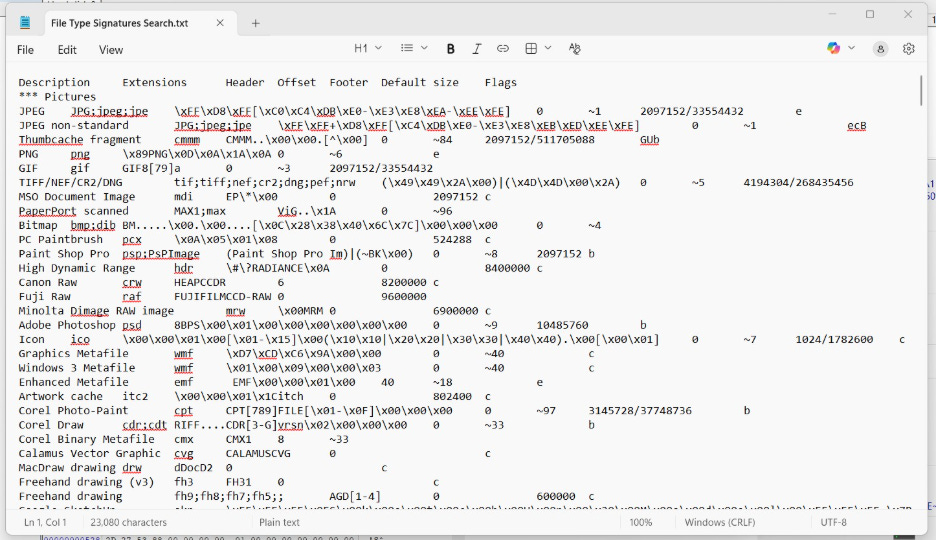

The first way a file type is identified is by the first few bytes in a file (something called a file signature or file header). These signatures are unique to that file type and identify the file to the application using it. The signature tells Microsoft Excel that this is an Excel spreadsheet file, the signature tells Adobe Acrobat that this is a PDF file. If you attempt to open a file of a certain type in an app for another type, you may get an error message saying the file is invalid for this app, or you may get a message asking you if you would like to try to convert the file, depending on the app and file type.

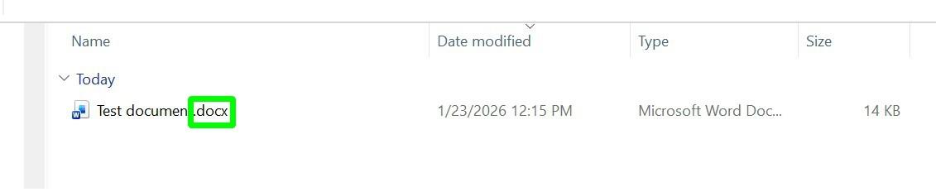

The second way a file type is identified is by the file name extension (those last three or four characters after the dot in the file name, such as .docx or .pdf). These file name extensions tell the operating system which application uses these files, so a .docx extension tells the operating system this file is used by Microsoft Word or a .pdf extension tells the operating system this file is used by Adobe Reader. This is how the “Default apps” setting works on a Windows computer. Double clicking on a file with a .txt file extension will cause the Notepad app to open that file, or double clicking on a .jpg file will open that file in the Photos app.

Files and file types contain all the information about what is going on in that specific device. Forensically speaking, by analyzing this information we can get clues about how this device was being used, and what it was being used for. Files are the lifeblood of a device as far as a forensic investigation goes. As important as it is for a doctor to collect blood for a medical examination, the importance is the same for a digital forensics analyst to collect files for a digital forensic examination. This is what makes forensic imaging (the copying of files on a device, usually called an extraction for mobile devices) critical for forensic investigations.

The forensic collection of files from a device depends on the access an analyst has to the device. In a best-case scenario, the analyst will be able to do a full file system (FFS) collection, which will contain all files used by the device. This gives the analyst the most complete view of the device. In some less optimal scenarios, only user files may be available, which gives the analyst less to work with in an investigation.

During a forensic investigation, there are many things an analyst can look at. Log files may tell which applications were in use at a certain time. Data files may contain documents, photos, or emails sent by a user. An analyst might also look for and examine a text message database to confirm what was found by a forensic tool.

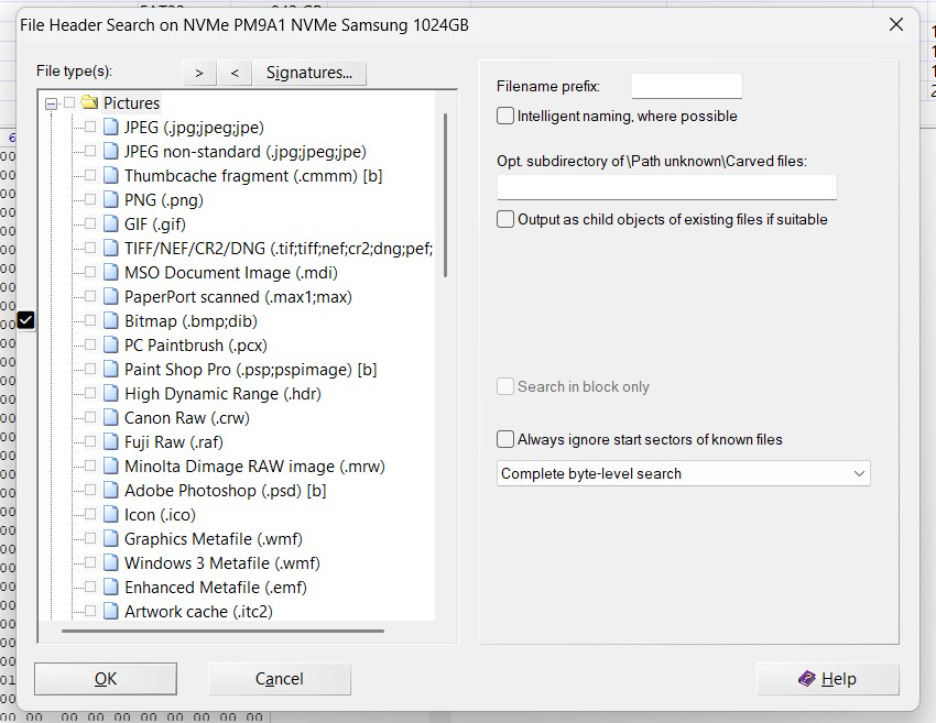

Another thing an analyst might do is look for deleted files using a process called file carving. File carving involves going through the storage space looking for known file signatures. WinHex is an example of a forensic tool that can do file carving.

If a signature is found, then the file carving tool will estimate where the end of the file may be and recover all of the data from the signature through the estimated end of the file.

There are also some things that can be done to try to hide files on a computer. If a user wanted to hide a Word document that had sensitive information, they might change the file extension from .docx to .dll or .exe to make it appear to be a system file by looking at the file name. An analyst would discover this attempt by examining the file signature (which could not be changed without affecting the integrity of the file).

Another trick called steganography means hiding one file inside of another file. For example, the format of a JPEG picture file has flexibility where there is free space in the file that is not used by the viewing application. A savvy person might take the data from a Word document and place it in this free space area of a picture file using a file editing tool. This Word document would now be out of plain sight but could be discovered by the analyst seeing a file having an unusually large size or by a file carving tool finding the file signature for the Word document embedded in the JPEG picture file.

These are just some of the things a digital forensics analyst may look at when examining a device, but the devil is in the details. And for these devices, the details are in the files and file types.

Chris Pelletier, Digital Forensics Analyst

Upcoming Events

February 2, 2026

AI & the Future of the Courts (NYSBA) (Virtual)

February 4, 2026

Age Verification Law and Policy (ABA) (Virtual)

February 5, 2026

EFF Town Hall: ICE, CBP, and Digital Rights (EFF) (Virtual)

February 6-7, 2026

CactusCon 14 (CactusCon) (Mesa, AZ)

March 9-12, 2026

LegalWeek (ALM Law.com) (New York, NY)

March 10-12, 2026

MSAB Mobile Forensics Digital Summit 2026 (MSAB) (Virtual)

March 12-13, 2026

2026 Privacy and Emerging Technology National Institute (ABA) (Washington, D.C.)

March 18-22, 2026

SANS OSINT Summit & Training 2026 (SANS) (Arlington, VA and Virtual)

March 22-29, 2026

NYC Open Data Week (NYC OTI, BetaNYC, and Data Through Design) (New York City, NY)

March 28-29, 2026

NYC School of Data (BetaNYC) (Queens, NY)

April 13, 2026

Legal Innovation & Technology Lab Conference (LIT Con) (Suffolk University Law School LIT Lab) (Boston, MA)

April 13-17, 2026

C2C User Summit 2026 (Cellebrite) (Washington, D.C)

April 20-22, 2026

Magnet User Summit 2026 (Magnet Forensics) (Nashville, TN)

April 23-25, 2026

19th Annual Making Sense of Science: Forensic Science, Technology & the Law (NACDL) (Las Vegas, NV)

May 12, 2026

Decrypting a Defense V Conference (Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit) (New York, NY) (Registration link coming soon!)

Small Bytes

Hacktivist deletes white supremacist websites live onstage during hacker conference (TechCrunch)

The Homeland Security Spending Trail: How to Follow the Money Through U.S. Government Databases (EFF)

Inside ICE’s Tool to Monitor Phones in Entire Neighborhoods (404 Media)

How Hackers Are Fighting Back Against ICE (EFF)

AI Didn’t ‘Unmask’ The Minneapolis ICE Shooter — It Invented A Face (Forbes)

Police Unmask Millions of Surveillance Targets Because of Flock Redaction Error (404 Media)

Bizarre twist in N.J. mansion murder trial: Fire marshal grilled for ChatGPT use (NJ.com)

ICE’s Facial Recognition App Misidentified a Woman. Twice (404 Media)

Surveillance and ICE Are Driving Patients Away From Medical Care, Report Warns (Wired)

Microsoft Gave FBI Keys To Unlock Encrypted Data, Exposing Major Privacy Flaw (Forbes)

Here is the User Guide for ELITE, the Tool Palantir Made for ICE (404 Media)

How ICE Already Knows Who Minneapolis Protesters Are (NY Times)

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. This analysis of secret watchlists is vital; understanding these surveillance pratices is crucial for human rights.

Exceptional breakdown of ALPR surveillance creep. The Norfolk case highlights how courts are drawing arbitrary lines between acceptable and unconstitutional surveillance when the tech itself is functionally indistinguishable. When 3 datapoints per day is ok but 101 isn't, we're just negotiating degress of dragnet surveillance rather than challenging the premise. Saw simiar reasoning in geofence warrant cases where judges split hairs on radius instead of addressing mass data collection.