August 7, 2023

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. In this issue, Joel Schmidt explores the NYPD’s new drone program and Shane Ferro reviews the continued rise of AI in law enforcement. Diane Akerman discusses the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act. Finally, Allison Young looks at the Citizen app with a forensic lens.

The Digital Forensics Unit of the Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of the Legal Aid Society.

In the News

Airborne Surveillance

Joel Schmidt, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

The NYPD recently announced its intention to deploy drones to broadcast announcements to the public during weather and other emergencies that create a disruption to power or telecom services. These drones are said to be equipped with the ability to broadcast audio messages to affected neighborhoods during an emergency.

But can we trust the NYPD not to modify the drones for surveillance purposes? History suggests no.

The NYPD has a long and sordid history of over-surveilling New Yorkers. From the 1950s through the 1970s the NYPD significantly surveilled many political organizations it disagreed with, so much so that over a half million index cards were needed just to catalog and cross-refence the dossiers they generated.

In the 2000s, the NYPD engaged in extensive spying and religious profiling of Muslims and Muslim organizations in New York City and beyond. They sent informants to report on conversations and sermons within mosques, monitored Muslim students throughout the Northeast, kept files on Muslims who changed their names, and even infiltrated and shadowed volunteers at a Muslim food bank – none of which ever generated a lead or triggered a terrorism investigation.

More recently, the NYPD has used advances in technology to ramp up their surveillance to levels previously unimaginable. They monitor a network of 18,000 interconnected NYPD and private sector surveillance cameras, deployed 500 automated license plate readers across New York City and has contracted with a private company for access to 12 billion nationwide license plate records allowing the NYPD to track New Yorkers across the country, and they aggressively monitor New Yorkers’ social media profiles.

One federal judge stated of the NYPD “it is a historical fact that as the decades passed, one group or another came to be targeted by police surveillance activity.” In the past the NYPD has tapped into a secret slush fund of money to finance its surveillance operations, and has failed to honor the spirit of the 2020 Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology Act (POST Act), requiring it to be transparent with the public about its surveillance technology purchases and capabilities. It has also rejected 14 of 15 surveillance transparency recommendations proposed by the Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD.

The NYPD tested these new drones last month but refused to release the results to the public. The NYPD has even avoided calling these obvious drones “drones,” possibly in an attempt to evade the POST Act’s requirements requiring the NYPD to seek public comment and release a public impact and use policy 90 days before acquiring new surveillance technology.

“This plan just isn’t going to fly,” said Surveillance Technology Oversight Project Executive Director Albert Fox Cahn. “The city already has countless ways of reaching New Yorkers, and it would take thousands of drones to reach the whole city. The drones are a terrible way to alert New Yorkers, but they are a great way to creep us out.”

Given how easy it is to modify drones for surveillance or even military purposes, and the city’s existing use of the Wireless Emergency Alert system, capable of broadcasting emergency messages to cellphones in a targeted area, the NYPD does not need these drones and we should not trust them not to use these drones to surveil New Yorkers under the guise of emergency preparedness. The NYPD already has drones in its possession it has apparently already misused. We should not sanction any more.

The Increasing Creep of Law AI-forcement

Shane Ferro, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

It seems you can’t throw a stone anymore without hitting a surveillance system powered by artificial intelligence.

In New York City, NBC News reported this month that the MTA has quietly started to implement an AI system to catch fare evasion in several subway stations across the city. The MTA claims that this will not be used for law enforcement purposes, but how it might impact the criminal legal system has yet to be seen.

According to NBC, the MTA is using software by Spanish company AWAAIT, which claims to “send photos of people it determined were fare evaders to the smartphones of nearby station agents” in promotional materials. AWAAIT’s website claims that the software “run[s] inspections only on fare infraction alerts without bothering fare-paying passengers,” and that artificial intelligence is used to differentiate between the two.

Separately, Forbes reported on the case of a man who was pulled over in Westchester in 2022 after an enormous cross-state automated license plate reader (ALPR) database flagged the car as having made several trips between New York and Massachusetts in a nine-month period “following routes known to be used by narcotics pushers and for conspicuously short stays.” The car stop was based on the car being flagged by the data, rather than any traffic violation that day.

The AI combing through the government’s ALPR data is made by a company called Rekor, which according to Forbes has sold its ALPR tech to “at least 23 police departments and local governments across America, from Lauderhill, Florida to San Diego, California.” The software scans for suspicious patters in the millions of license plates that each jurisdiction captures week after week, month after month. According to Forbes, Westchester County alone has 480 cameras scanning 16 million license plates a week. (Unsettlingly, at least two of those per week are probably this author’s—are any of them yours?)

The increasing availability of 1) enormous dragnet surveillance datasets and 2) software that can actually parse that much data coincides with law enforcement increasing the use of Real-Time Crime Centers, as Wired reported on earlier in July.

The New York State Bar Association seems to recognize that AI is something that the legal field is going to need to start grappling with. In July, it announced a new task force on “emerging policy challenges related to AI.” NYSBA’s news release on the new task force notes that there are many ways in which AI may change the legal profession, including ways it could be helpful for lawyers. However, it “will also have a dramatic – and yet to be determined – impact on copyright, patent, and privacy laws.”

Unfortunately, it’s unclear that Americans will have any privacy left by the time the law catches up to the data.

Policy Corner

Surveillance Capitalism is the New Exception to the Warrant Requirement

Diane Akerman, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

A lot of ink has been rightfully spilled over the modern plague of data brokers profiting off of individual’s personal information. As we move rapidly from individual attacks on bodily autonomy to wholesale criminalization of abortion and gender affirming care, the focus has centered on the ease with which private health data is so easily leaked, bought, and sold. HIPAA, you say? Much of the data shared or stored on health and wellness apps often exist in a grey area, unprotected by HIPAA [PDF].

Turning people into profit by trading in private data is unsettling in and of itself, but this information in the hands of the carceral state is downright dangerous. But at least we have the Fourth Amendment to protect this data from warrantless searches and seizures by the government, right?...right?

A report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) found that law enforcement regularly subverts the warrant requirement by simply purchasing otherwise constitutionally protected information from data brokers. The government’s justification?

[B]ecause companies are willing to sell the information—not only to the US government but to other companies as well—the government considers it “publicly available” and therefore asserts that it “can purchase it.”“If it’s for sale, it ain’t private” is, after all, the logical conclusion to the Third-Party Doctrine.

The report prompted a group of bipartisan lawmakers to introduce the Davidson-Jacobs amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) – known as the bipartisan Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act. The Act “stops the federal government from circumventing the Fourth Amendment right to privacy by closing loopholes that allow the government to purchase Americans’ data from big tech companies without a search warrant.” It also prevents law enforcement from buying data from abroad, obtained by hacking, or in violation of terms of service or privacy policies - resulting in a complete prohibition of purchasing data from Clearview AI, once and for all. (They are still bad, in case you forgot). The Act has garnered significant support from lawmakers, but The National Security Agency (NSA) unsurprisingly, is not thrilled.

Now if only the process for getting a warrant was actually any harder than just buying the data.

Ask an Analyst

Do you have a question about digital forensics or electronic surveillance? Please send it to AskDFU@legal-aid.org and we may feature it in an upcoming issue of our newsletter. No identifying information will be used without your permission.

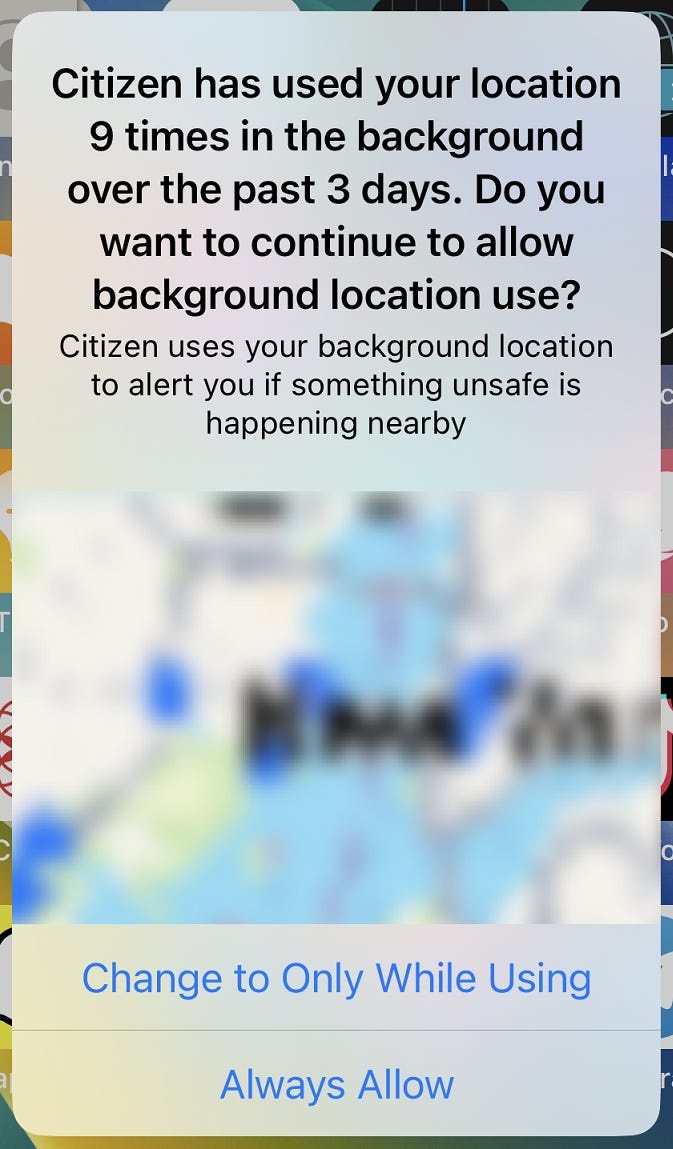

Q: There is a video of an incident that was posted to “Citizen” and is relevant to my case. However, when I try to access it, I can’t play or download it – I can only see notes about the incident. Is there a way to preserve this data?

A: Citizen is a news and safety app that got its start in NYC (as “Vigilante,” which was then banned in the app store in 2016 before relaunching) but has since then expanded to major urban areas across the United States. Events are sourced from a combination of app user eyewitness reports, including phone video footage, and the filtered output of information gleaned from police scanner activity. Users can “explore” events in a geographic area for free, but need an account to comment, react, post their own videos, or access any of the other features made available in the app. Videos of incidents that are posted to the app are reviewed by a content moderation team before being shown on the platform, and one reported incident can have multiple videos and comments associated with it.

Without paying for a membership, videos on Citizen expire in 7 days. That means that if more than a week has passed since the video was posted, you will be able to see the incident title, comments, and a blurred preview of any videos, but you will not be able to download it.

Users who pay for Citizen Plus can access 90 days of footage and audio clips of police scanner transmissions related to incidents. Users who pay for the Premium appear to be able to access and download any video from any point in time (as well as “Protect” features, where Citizen monitors a user's location and is able to assign a safety agent to call 911 on their behalf if necessary. Citizen also tested a private security force two years ago that they have since disbanded.

The app is susceptible to misinformation and has been the subject of controversy. Citizen was in the news for offering a reward to find a man who turned out to be falsely accused of arson. They’ve also been criticized for deploying freelance workers to film, or even intervene in, events without disclosing that they are paid workers and not regular users, including accusations of sending street team members to the January 6th Capitol Riot.

Citizen relies on accessing user’s location information to send alerts on incidents in the area and for its Protect private safety service. Additionally, you can add “friends” on the Citizen app and access their location and phone battery level in real time – similar to Apple’s Find My Friends feature. While we have not yet received a return from Citizen, their Law Enforcement Guide indicates that a warrant return "may include messages, photos, videos, chat messages, and location information.”

Allison Young, Digital Forensics Analyst

Upcoming Events

August 3-11, 2023

Digital Forensics & Incident Response Summit & Training 2023 (SANS) (Austin, TX & Virtual)

August 8-9, 2023

BSides Las Vegas (Las Vegas, NV & Virtual)

August 10-13, 2023

DEF CON 31 (Las Vegas, NV)

Check out the talk from the Digital Forensics Unit’s own Allison Young and Diane Akerman, “Private Until Presumed Guilty”

September 11-13, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference West (Pasadena, CA)

Check out the presentation from the Digital Forensics Unit’s own Brandon Reim, “Path of a Defense Case”

September 22, 2023

SANS OSINT Summit 2023 (SANS) (Virtual)

October 10, 2023

AI Admissibility and Use at Court Hearings and/or Trials (NYSBA) (Virtual)

October 19, 2023

The Ethics of Social Media Use by Attorneys (NYSBA) (Virtual)

Small Bytes

US Spies Are Buying Americans’ Private Data. Congress Has a New Chance to Stop It (Wired)

NYPD push for cell phone ID numbers worries civil libertarians (NY Daily News)

Bronx District Attorney Expanding Phone-Cracking Technology (The City)

The NYPD doesn’t report where it deploys police. So scientists used AI, dashcams to find out. (Gothamist)

Why Dayton Quit ShotSpotter, a Surveillance Tool Many Cities Still Embrace (Bolts)

The Polygon and the Avalanche: How the Gilgo Beach Suspect Was Found (NY Times)

Top tech firms commit to AI safeguards amid fears over pace of change (The Guardian)

Tightening Restrictions on Deepfake Porn: What US Lawmakers Could Learn from the UK (Tech Policy Press)

Texas State Police Purchased Israeli Phone-Tracking Software for “Border Emergency” (The Intercept)