AI & Photography, NYC Council Hearing, Geofence Warrants, Search Warrant Returns, & More

Vol. 4, Issue 5

May 1, 2023

Welcome to Decrypting a Defense, the monthly newsletter of the Legal Aid Society’s Digital Forensics Unit. In this issue, Allison Young discusses artificial intelligence and photography. Diane Akerman talks about a NYC Council hearing on biometric bans. Joel Schmidt explains geofence warrants. Finally, Lisa Brown answers a question about digital device search warrant returns.

The Digital Forensics Unit of the Legal Aid Society was created in 2013 in recognition of the growing use of digital evidence in the criminal legal system. Consisting of attorneys and forensic analysts, the Unit provides support and analysis to the Criminal, Juvenile Rights, and Civil Practices of the Legal Aid Society.

In the News

Fake Moons, Smartphones, and Computational Photography

Allison Young, Digital Forensics Analyst

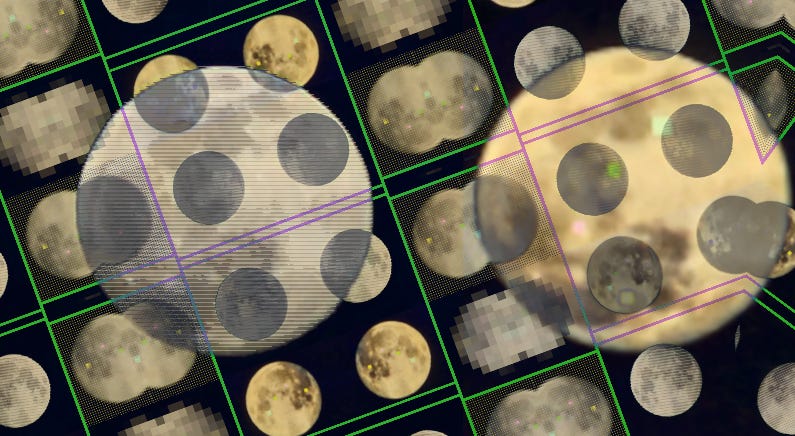

Last month, a Reddit user published evidence suggesting that Samsung’s 100x Space Zoom has been marketed in a misleading way. The feature combines multiple cameras and some algorithmic magic to provide an effective “100x” zoom on some models, resulting in beautiful photos of the moon. The only problem? It looks like details of the moon’s surface are being added into the photo by the phone – leading some to wonder what else could be added into their own photos without their knowledge.

This may remind you of a similar issue 4 years ago when a researcher claimed they had evidence that Huawei’s Moon Mode was overlaying images of the moon onto photos (an allegation which Huawei denied). Samsung’s answer was similar to theirs, confirming that AI was to credit and to blame depending on who you ask, but the explanation still leaves room for confusion. What is going on with phones these days?

Smart phones rely on impressive computer math to automatically enhance the images you capture with the devices. iPhones and other smart phones take multiple shots and combine them into one photo to improve detail. Object recognition in a photo may trigger different processing decisions, like blurring a background in portrait mode or changing color levels. These features and others aim to remove heavy hardware and a subscription to Adobe Photoshop from the photo-taking experience. Machine learning replaces the human photography expert with a pocket-sized one, making anywhere from tens to millions of decisions without needing your input. How those decisions are made is usually a “black box” to the end consumers.

If you’ve followed the news in the last few years, you probably know that machine learning and ethical issues go together like April Showers and May Flowers, as detailed in this recent article by the Washington Post. We also know that AI can mistake a window for Ryan Gosling.

While media enhancements can be useful for clarifying details in an image, something as simple as resizing an image can potentially introduce artifacts, or errors, into an image (including pixels that may give the impression of a lunar surface). When performing media enhancements for use in the courtroom, an expert should document all changes to an original image so that another expert can perform the same steps and obtain the same output. Digital evidence is subject to the Frye standard in New York courts, but innovation in consumer tech is not subject to the same scrutiny.

I’m not suggesting that this is currently a serious issue for the authenticity of all digital photos admitted into evidence – the NYPD, last I checked, does use real cameras to capture images of crime scenes. Questioned images can be analyzed to try to show tampering or overly prejudicial enhancements. However, it’s concerning that we are living in an age where what a witness captured with their smart phone is not necessarily what they saw, and that they may not be able to tell the difference.

Up to this point, the introduction of AI into improving digital photography has been quieter than recent AI horror stories news coming from language models like ChatGPT or flashy tools that create deep fake imagery. Criticism of Samsung’s “Space Zoom” highlights the fact that consumers, attorneys, their clients, judges, and juries may not consider what is going on “under the hood” when presented with a digital image on a phone. Worse still, issues like these may only get harder to catch.

“They Wouldn’t Use It If It Wasn’t Reliable”

Diane Akerman, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

Convictions based on junk science have plagued the criminal legal system in forensic fields. Experts testified about things like bite-mark analysis and polygraphs, presenting them to juries as reliable beyond a reasonable doubt. The field of digital forensics faces a similar problem with one huge difference – many of the unreliable technologies we encounter in cases are widely available to consumers, who have come to trust the tech for security or simply convenience.

Fingerprints or face ID have become ordinary methods of unlocking one’s device. Banking institutions use voice recognition for consumer security for mobile banking. Many people have enjoyed playing around with AI art and ChatGPT. The NYPD isn’t the only entity with a giant budget to secretly purchase surveillance tools without oversight for years. What about all the private corporations? The banks? Building security? Amazon? Or just simply, a petty billionaire?

There’s a Grand Canyon sized chasm between your bank using voice recognition as a security feature, and the government using unreliable technology to arrest and prosecute. As we welcome more of these technologies into our lives, we are socialized to trust them, and that trust is exploited by law enforcement agencies who hide the ball, and prosecutors who sneak in testimony at trial.

On May 3, 2023 at 1:00PM EDT the New York City Council Technology, and Civil and Human Rights Committees are holding a hearing on two bills aimed at limiting the pervasiveness of biometric monitoring in our daily lives. The first bill, sponsored by Shahana Hanif (District 39, Brooklyn) seeks to ban the use of biometric surveillance in public accommodations – places like sports arenas, retail stores, and restaurants – to verify the identity of a customer. The law also establishes requirements for disclosure and retention of such data and requires that businesses have detailed written policies regarding its use. The second bill, sponsored by Carlina Rivera (District 2, Manhattan) makes it unlawful for the owner of a multi occupancy building to install or use any biometric technology to identify tenants or guests.

Regular readers of the newsletter will know that we here at the Digital Forensics Unit are no fans of facial recognition technology. We really, really can’t stop talking about how much we want it banned and how something this unreliable certainly shouldn’t be used as the basis for an arrest. What we maybe haven’t made clear is that we also don’t recommend throwing away your house key just yet. There’s no safety in unreliability.

In the Courts

Geofence Warrants and the Fourth Amendment

Joel Schmidt, Digital Forensics Staff Attorney

We all know what a fence is, but do you know what a geofence is? Do you know what a geofence warrant is?

Imagine you went to an online map of New York City and used your mouse to draw a virtual line around Times Square. You will have created a geographical fence, or geofence, of Times Square. A geofence warrant would compel a company (most typically Google) to disclose every single cellphone sending location data to the company and known to be within the boundaries of the geofence – in this case Times Square – for the specified time period. A geofence doesn’t have to be a circle. It can be any size or shape, or even a straight line between two points. A geofence warrant should be narrowly tailored to keep privacy violations to an absolute minimum.

In a recent case [PDF], a California appellate court held that the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department prepared, and a judge signed, a geofence warrant that unconstitutionally infringed on the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Sheriff’s Department was investigating the homicide of an individual who they believed had been followed by two cars to six separate locations prior to the incident. They drew up a geofence warrant signed by a judge. Via a three-step process the warrant compelled Google to identify all individuals whose location history indicated they were at the identified locations during the specified time periods.

First, Google had to produce an anonymized list of all cellphones within any of the locations for the specified time periods. Then, the Sheriff’s Department could request additional location data for any of the phones, including location data that fell outside the specified location and time parameters. In the final step, the Sheriff’s Department was able to request identifying information for any cellphone it unilaterally deemed relevant to the investigation.

The Court held that the unbridled discretion in steps two and three allowing the Sheriff’s Department to unilaterally seek additional location and identifying information on any device it choose, without any court oversight, did not comport with the law. “This failure to place any meaningful restriction on the discretion of law enforcement officers to determine which accounts would be subject to further scrutiny or deanonymization renders the warrant invalid.”

The court also invalidated the warrant because the geofences and timeframes were all far larger than they needed to be. “While we recognize it may be impossible to eliminate the inclusion of all uninvolved individuals in a geofence warrant, it is the constitutionally imposed duty of the government to carefully tailor its search parameters to minimize infringement on the privacy rights of third parties.”

As digital technology becomes more pervasive, we must remain vigilant to ensure law enforcement is not permitted to exploit new ways to invade our privacy. Courts must intervene when agencies push the envelope to violate our privacy rights in ways previously unimaginable.

Ask an Analyst

Do you have a question about digital forensics or electronic surveillance? Please send it to AskDFU@legal-aid.org and we may feature it in an upcoming issue of our newsletter. No identifying information will be used without your permission.

Q. I was just served with a cell phone warrant and its returns. The warrant is limited to phone contents from January 2020. I’m reviewing the returns in Cellebrite Reader, and I am seeing photos from 2017, 2018 and 2019. What’s going on here?

A. Often, this is a prime example of how the language in a search warrant doesn’t always have a clear technical translation. Most photos will have several timestamps associated with them, not just the date the image was photographed.

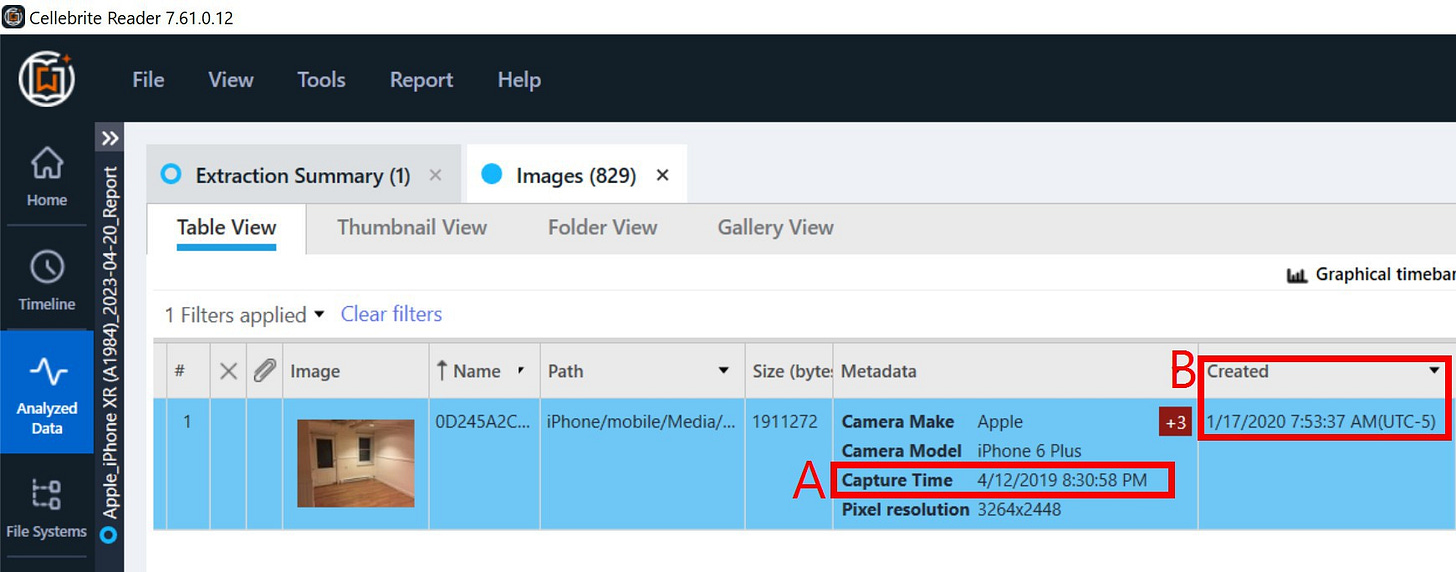

When a photograph is captured with a smartphone, the camera app embeds the current date and time within that photograph’s internal metadata. Cellebrite labels this value as “Capture Time” (marked “A” in this example below). Separately, the phone’s file system stores several timestamps associated with each file on a phone. One of those timestamps is called the “Created” date (labeled “B” in this example), and that refers to the date and time the file is created on the phone. Although the “Created” date will initially match the photograph’s capture time, there are many situations where this “Created” will reflect something completely different.

In this example, a photograph was captured on April 12, 2019 on an iPhone 6 Plus. On January 17, 2020 the phone user traded in their iPhone 6 for an iPhone XR and restored an iCloud backup to the new phone. While the new phone maintains the image’s original “Capture Time” from 2019, the “Created” date is set to the date of the restore, because the file is new to the iPhone XR.

Additionally, if someone receives a photograph by text message or downloads a photo from social media, their phone will assign a new “Created” date for the image, because the phone sees it as a new file. If an image was received, downloaded, or restored within the timespan of the search warrant parameters, it will get included in the returns even though the photograph may not have been captured during that time.

Legal Aid attorneys who receive a cell phone search warrant return that appears to contain files outside the scope of the search warrant, should reach out to the Digital Forensics Unit. We can help investigate why these files may have been swept up in the search filter, and whether there are any possible legal challenges.

- Lisa Brown, Senior Digital Forensic Analyst

Upcoming Events

May 2, 2023

Introduction to AI: “Tech” Session (NYSBA) (Virtual)

June 5-8, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference East (Wilmington, NC)

August 3-11, 2023

Digital Forensics & Incident Response Summit & Training 2023 (SANS) (Austin, TX & Virtual)

August 10-13, 2023

DEF CON 31 (Las Vegas, Nevada)

September 11-13, 2023

Techno Security & Digital Forensics Conference West (Pasadena, CA)

Small Bytes

ICE is Grabbing Data From Schools and Abortion Clinic (Wired)

City Council calls for security cameras, more patrol officers in NYC parks (Gothamist)

Special Report: Tesla workers shared sensitive images recorded by customer cars (Reuters)

AI clones teen girl’s voice in $1M kidnapping scam: ‘I’ve got your daughter’ (NY Post)

New York City’s Techno-Authoritarian Mayor Unveils New Police Robots (Tech Policy Press)

NYPD may be violating police surveillance transparency law (City & State NY)

Robot Lawyers Are About to Flood the Courts (Wired)

Spyware Company NSO Exploits Find My iPhone Flaw In Zero-Click Hack (Forbes)

Palantir Demos AI to Fight Wars But Says It Will Be Totally Ethical Don’t Worry About It (Vice)